Independent Thinking®

Connecticut at the Crossroads

February 2, 2016

GE’s announcement on January 13 that it plans to move its headquarters to Boston from Fairfield, Connecticut, publicized on a national level what residents of the Nutmeg state have known for some time: Connecticut is struggling to grow its economy while funding necessary services and legacy costs.

While the state continues to grapple with its budget, investors in the state will need to be extremely selective in their exposures.

Background

Connecticut is recovering from the 2008 financial crisis at a slower rate than the New England region and the United States as a whole. It is still the wealthiest state in the nation on a per capita basis, with a highly educated population and low poverty levels, which spares it from spending much on costly service programs1.The state has finally recovered 100% of the private sector jobs it lost during the recession, though some key sectors continue to show negative employment trends from a year ago, including information and financial activities. However, Connecticut’s dependence on its wealthy residents, who feel the impact of capital gains, keeps the state extremely vulnerable to financial market fluctuations.

While Connecticut does have the legal ability to raise revenues, and has obviously exercised that ability on numerous occasions, there are limits. Several high-profile corporations have expressed their displeasure with certain new taxing proposals, notably Aetna and Travelers, in addition to the GE management now voting with their feet. Also troubling is the difficult situation of the state’s rising fixed funding costs, particularly in employee-related pension and healthcare that are outpacing revenue growth. More benefit reforms may be needed.

And Then Reality Hit

The obvious and legal requirement of the governor and legislature is to submit a balanced biennial budget, which was approved just prior to the beginning of the fiscal year that started on July 1, 2015. To balance the budget, the state relied on another round of various tax increases totaling over $1.3 billion, while canceling another $500 million in previously approved tax cuts. In trying to avert more deficits, the legislature approved a provision that requires automatic deposits into the emergency budget reserve whenever the state’s income or corporation taxes take in more than budgeted amounts. It also increased the amount the state can set aside to 15% from 10% of the general fund.

This solution hasn’t gone according to plan, however. The legislature’s non-partisan Office of Fiscal Analysis in November 2015 projected a $252 million deficit for this fiscal year ending June 30, $552 million for the next fiscal year, and $1.72 billion for the following year, or 8.5% of operating expenditures.

It rightly troubles investors in the state that these projected deficits arose so quickly after the biennial budget was set and that taxes were raised significantly, yet again, in an attempt to provide recurring revenues. Closing the current year’s budget gap is primarily derived from diverting other specialized funds. Tapping temporary resources to pay for annually recurring expenses, such as the Special Transportation Fund and the funds allocated to cities and towns, public colleges and universities, doesn’t strike us as an ideal approach. The administration stated that it will also make across-the-board expenditure cuts but has not released specifics.

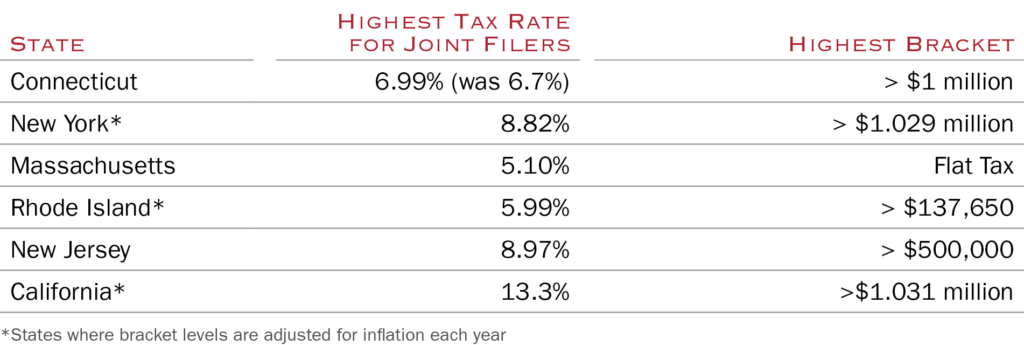

In the interim, the top income tax rate in Connecticut is getting high by neighboring Rhode Island and Massachusetts standards, but is still lower than in its tri-state partners of New York or New Jersey. It’s also lower than in California, a state that has still experienced significant economic growth.

We attribute this budgetary deficit to two main drivers: substantive overestimations by the state of volatile personal income tax receipts without significantly reducing expenditures; and a pressing need to increase pension funding. (See the “Tax and Budget Appendix” for details on Connecticut’s biennial budget.)

State Pensions

Pension liabilities have also become a burden for Connecticut, although the state has made some progress in addressing this issue. Employee and teacher retirement plan state payments are reflected in the current budget, and the state is now required to maintain full funding of the annual required contribution going forward. To date, and unlike New Jersey, Connecticut has fulfilled that requirement with some slight improvement to still large liability levels.

The state had commissioned the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College to report on the State Employees Retirement System, or SERS, and the Teachers’ Retirement System, or TRS. The unfunded actuarial accrued liability, or UAAL, is

- 42% funded for SERS and UAAL of $14.9 billion; and

- 59% funded for TRS and UAAL of $10.8 billion

Three factors have contributed to this shortfall:

- Legacy costs from benefits promised before the systems were pre-funded (not until 1971 for SERS and 1982 for TRS)

- Inadequate contributions since the state decided to pre-fund

- Low investment returns relative to the assumed return since 2000 (only 5.6% annually for both, compared with an assumed return of 8.5% for TRS and 8% for SERS)

The study showed that, based on current planned funding, this year’s $1.8 billion pension contribution could almost quadruple by 2031, hitting $6.65 billion before dropping to $400 million a year. Governor Dannel Malloy is proposing to change the funding by keeping annual pension costs at $2 billion a year, starting around fiscal year 2019. In deferring payments, there is a missed opportunity to invest funds and achieve additional earnings. It’s also worth noting that these changes will need to be negotiated with state employee unions.

Infrastructure

Transportation infrastructure funding has become another financial burden, not just for Connecticut but for the country as a whole. The American Society of Civil Engineers report on all states includes these observations on Connecticut’s transportation infrastructure2:

- 413 of the 4,218 bridges are structurally deficient

- $1.6 billion a year in costs to motorists from driving on roads in need of repair, which is $661 a year per motorist

- 41% of the state’s 3,350 major public roads are in poor condition

- 41.4 million annual unlinked passenger trips via transit systems, including bus, transit and commuter trains. This complicates travel and discourages mass transit use.

The governor’s goal is to provide for a new statutory lockbox that establishes the State Transportation Fund as a perpetual fund solely for transportation purposes and prevents the state from raiding the fund to balance the state’s general operating fund.

Connecticut residents should be prepared for the potential increase in various user-based revenue fees, including motor vehicle receipts, licenses and permits, gasoline tax, rail and bus, congestion mitigation tolling and so-called value capture, which allows the state to try to capture increase in land value near transportation improvements.

Connecticut Bonds

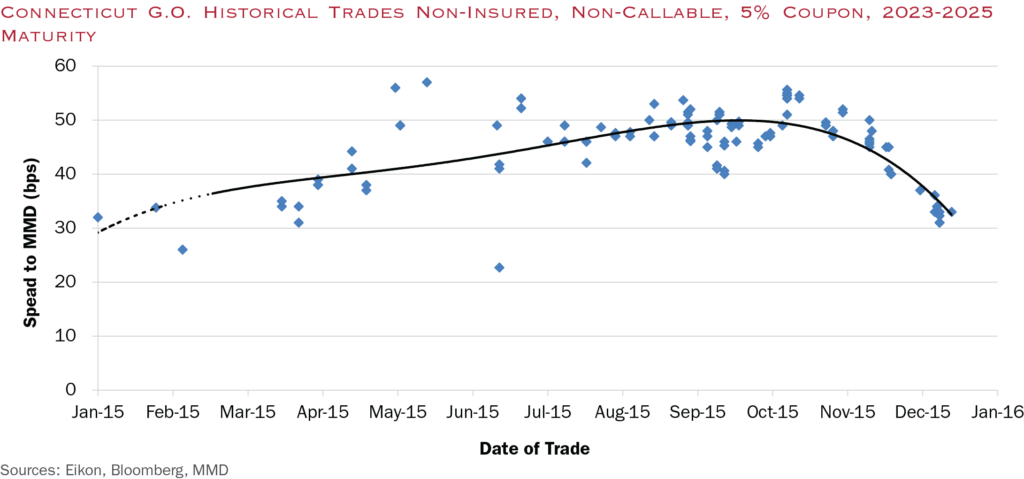

Connecticut bonds retain strong investor demand, due to the state’s high wealth levels and increasing income tax rates. It also helps that there is relatively little choice: The state assumes much of the capital improvement programs for school districts and municipalities with no active county government, leaving few credits to choose in the market, relative to other states. Consequently, as shown on the chart below, spreads for Connecticut general obligation debt compared to the triple-A municipal bond scale have widened for much of 2015 but not to the same extent as other pension burdened states, such as New Jersey and Illinois. We believe recent narrowing of Connecticut spreads reflect overall market conditions rather than improved state credit characteristics.

GE’s move north has come as a huge shock to Connecticut legislators. This same dissatisfaction is felt at the household level too: The absence of significant cuts on the expenditure side makes tax increases less palatable to many of Connecticut’s citizens. There is a recognition that, unless state expenditures, including pension obligations and health benefits, are curtailed, additional tax increases are inevitable.

The budget assumes $500 million in new tax receipts from Connecticut income taxpayers, created by a new marginal income tax rate of 6.9%, up from 6.7% for couples earning more than $500,000 and singles earning more than $250,000. For couples earning above $1 million and singles earning above $500,000, the new rate is 6.99%, up from 6.7%. Connecticut residents pay an income tax based on gross income, which includes capital gains, dividends and interest income. The proposal to create a 2% supplemental tax on capital gains income for the same filers was not implemented.

Conclusion

For Evercore Wealth Management clients, we have managed to find either strong local Connecticut credits, or statewide credits that are not burdened by some of the issues consuming the state. These names include Connecticut State Revolving Fund, Connecticut Housing Finance Authority, Connecticut Municipal Electric Energy Cooperative, South Central Regional Water Authority, Yale University, and local general obligation issues including Danbury, Darien, Norwalk, Ridgefield, Stamford, Trumbull and Westport. Other than Yale University, one of the most elite and financially stable institutions of higher education in the world, the entities listed are currently viewed by us as high quality owing to their own reliance on their tax base, rather than on the state, as well as a stable financial position. That is not to say that some state credits are to be avoided. However, there is a possibility of continued spread widening if the budget and pension liabilities do not become structurally balanced.

Tax and Budget Appendix

Here is a more detailed list of various tax and budget changes adopted in 2015. Besides the changes in income tax rates noted above, these include the following:

- Increase in sales tax rate on certain luxury items including motor vehicles (> $50,000), jewelry (> $5,000), clothing, handbags, luggage and footwear (> $1,000) to 7.75% from 7%.

- Reduction from $300 to $200 in the maximum credit households can claim against the income tax to help offset local property taxes. This is not available to upper-income households and will cost middle-income households about $100 million in fiscal year 2017.

- Cancellation of the sales tax exemption on clothing and footwear under $50 – costing consumers about $280 million over the next two fiscal years. A two-stage increase in the cigarette tax of 25 cents each in fiscal years 2016 and 2017 to total $3.90 by July 2016, generating $43.2 million.

- There is one small income tax cut in the budget. The state will now exempt all military retirement pay from the income tax. Currently only 50% is exempt; this will save veterans $10 million over the two-year period.

- The state’s sales tax will remain at 6.35% for consumers, but 0.5% of the tax will be set aside for transportation initiatives and another 0.5% will be earmarked for the first time for cities and towns generating over $500 million over the next two fiscal years. (Connecticut cities and towns, which currently receive a little more than $3 billion per year in statutory state grants, generate most of their additional revenue through the local property tax.)

- Another portion of the sales tax receipts will be used to enhance Connecticut’s system for reimbursing cities and towns for a portion of the revenue they lose because of tax-exempt property owned by the state, private colleges or hospitals. To receive the full grant under the program, towns must remain within a 2.5% spending cap to avoid using these funds as simply a windfall.

- Arguably the most controversial change – and one that already has been delayed for one year – concerns requiring corporate unitary reporting. At issue is how companies with operations in multiple states report their corporate income. In the past, companies in Connecticut generally had to report only the earnings of their in-state operations. Now the state will compel companies to share information on all of their operations – both in Connecticut and outside – and undergo a more detailed assessment of what profits are tied to their presence in Connecticut. (New York already requires companies with multistate operations to combine their profits, and then attributes a portion of those profits to New York.)

- The 20% surcharge on the corporation tax income filers with gross income above $100 million, which was supposed to expire in 2013, and then again in the new budget, was extended for two more years at its current rate and is now expected to phase out after fiscal year 2017.

- The final budget canceled plans developed previously to raise the sales tax rate on data processing and Web development services, which drew heavy criticism from business lobbyists and major corporations. This could have had a big impact on health insurers like Aetna, which increasingly sees itself as a data company.

- The budget included $19.8 billion in spending for the 2015-16 fiscal year and $20.4 billion in 2016-17. The rate of spending growth in the general fund, the state’s main spending account, increased 3.9% in the first year and 3.0% in the second. It restored some funding to many of the social service programs that Governor Malloy had cut in his original budget proposal, including mental healthcare and services for people with disabilities, state parks and the Connecticut State Colleges and Universities.

Howard Cure is the Director of Municipal Research at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at: [email protected].

12015 Connecticut Economic Review published in conjunction with Eversource Energy, the Connecticut Resource Center, Inc. and the Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development.

2America Society of Civil Engineers 2013 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure.