Independent Thinking®

The Growth Cycles of Private Equity

February 12, 2018

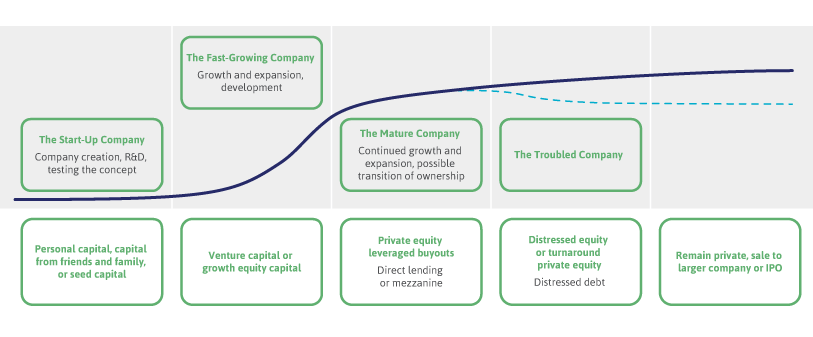

Funds that invest in illiquid securities lock up capital, usually for five to 10 years, but have the potential to outperform public markets. Based on where they are in their life cycle – from an idea hatched in a garage to a multinational corporation – companies will need different amounts and types of capital. Let’s look at what that private equity capital actually does.

The Start-Up Company

Most companies start small, with an idea or technology or service. To test that concept, or to begin building their business, the owners need capital. Many start with personal capital and sweat equity, but often they need additional capital from outside sources. They can borrow the money, usually with a personal loan, or they can sell a portion of the business. This seed capital can range from $10,000 to $1 million, as long as it’s enough to test the concept, found the business, and grow it into a sustainable concern. Traditionally, this was provided by friends and family, angel investors or early-stage venture capital. Recent developments such as crowdfunding and initial cryptocurrency offerings have democratized funding sources for entrepreneurs. The failure rate is high, but the potential return can be significant.

The Fast-Growing Company

Many small businesses can continue to fund growth through personal investments or through cash flows from the business. Owners of companies that require additional investments of more than $1 million will turn to institutional investors, such as venture capital or private equity.

Venture capital firms usually focus on early stage or pre-revenue companies, particularly those that are developing new technologies or business models with the potential to scale significantly or disrupt their markets. Venture capital firms provide funding between $1 million and $10 million, and take a minority stake in the business, leaving the founding partners as majority owners. Facebook is one of many companies, including Snap, Dropbox and Stitch Fix, that started with funding from venture capitalists. In addition to providing capital, venture capital firms often provide expertise to help start-ups refine their business plans and/or bring products to market. At times, these firms will bring in additional management or operational specialist and industry advisors to support the company as it grows.

Once companies are established, they often hit a period of high growth and need an infusion of capital for expansion. Growth equity firms focus on companies in the intermediate stage between start-up and established businesses. A successful manufacturer that needs capital to expand its production capacity, or a successful software company that launches a new product and needs to build out a national sales force, are two examples. Whole Foods accessed growth equity capital to expand from a regional organic grocer to a national footprint, growing both through acquisitions of existing grocers and through opening new stores. Private equity firms that focus on the growth equity stage usually invest $10 million to $50 million in the business and take a minority equity ownership stake.

The Mature Business

Established businesses have several options for funding expansion or capital investments. They can use cash flows from their existing businesses, they can borrow money, or they can sell an additional portion of equity ownership in the company. Private equity firms, or buyout firms, purchase a majority or 100% of a company’s equity ownership or voting stock, and take control of a company’s assets or operations. Private equity firms usually buy the ownership from the founders and their early seed capital backers. This can be a way for the founding partners to exit the business, or they can stay on in a management role but monetize their sweat equity. To purchase the company, private equity firms use a combination of equity and debt; those transactions that use substantial debt are called leveraged buyouts. The use of leverage is common in private equity buyouts, and although it can increase returns for the investors, it also adds a certain level of risk as the company now has to be able to service the additional debt. Many well-known public companies, such as Netflix, Burger King, Trivago and Alibaba, had private equity backing earlier in their lives.

Direct lenders focus on mature businesses and provide capital, usually through senior loans secured by the assets of the business (i.e., first lien loans). In the past, banks provided these types of loans to companies, but due to increased regulation, banks have pulled back their lending activity. In the last decade, private direct lending funds have stepped in, particularly in the middle market and privately held companies.

Mezzanine debt loans are lower in the capital structure, usually unsecured loans that rank below senior debt and above equity. Mezzanine lenders target the same middle market companies as direct lenders, but those with cash flows or assets that can support additional leverage.

The Troubled Company

Not all companies are successful, and some industries and businesses experience significant changes or disruptions. A distressed company is one that is no longer making a profit, has possibly defaulted on its debt, and needs a capital infusion to right the ship. Private equity firms that focus on special situation or turnaround investing take a controlling equity position in a distressed company that they believe they can turn around or set on a path to profitability. This is usually accomplished through cost cutting, strategic repositioning and/or other operational improvements, and sometimes involves bringing in a new senior management team. Many companies relied on capital from turnaround private equity firms in the aftermath of the global financial crisis to update manufacturing and operating efficiencies.

Alternatively, some investors target the debt of a distressed company. Distressed debt managers target companies likely to enter into a restructuring process and accumulate a debt position in order to influence the restructuring process or control the company post-reorganization. This process is often referred to as “loan to own.” Once in control of the reorganized entity, the manager usually implements the same cost cutting, strategic positioning, and operational or management improvements that turnaround investors make.

All along the life cycle of a company, there are a variety of capital sources from private equity buyers and lenders. Some companies remain privately held; some are sold to larger companies; while others ultimately grow large enough to become publicly traded through an IPO. Investors able to allocate a portion of their portfolio to illiquid assets should allocate to a range of illiquid opportunities – from illiquid credit strategies to venture capital to real estate – at different stages in their life cycles.

There are considerable opportunities in the private equity markets, but diversification is key. At Evercore, we diversify our investments in illiquid assets across a variety of asset classes, including direct middle market lending, private real estate, private equity, software buyouts, commercial solar generation, healthcare royalties and specialty finance.

Stephanie Hackett is a Managing Director and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. She can be contacted at [email protected].