Independent Thinking®

Public versus Private Companies: Weighing a Changing Dynamic

November 7, 2018

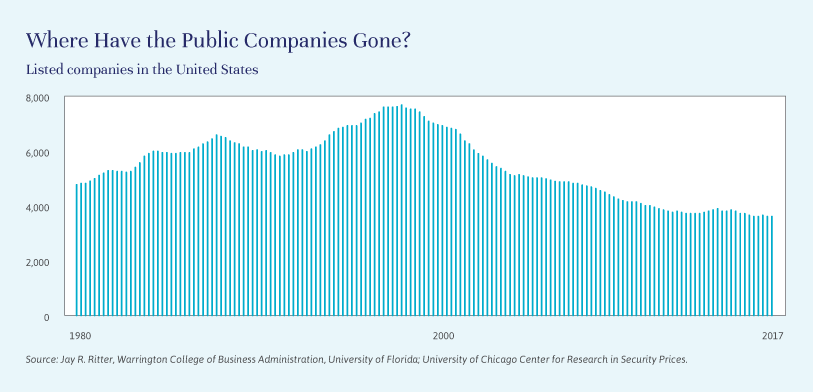

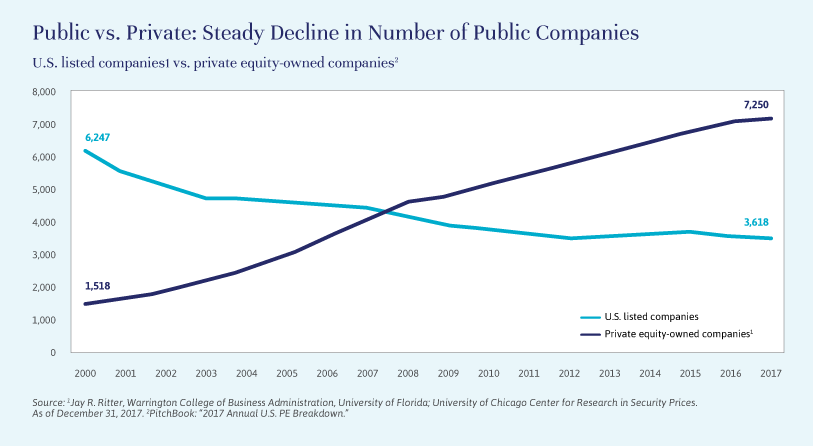

Equity markets have evolved dramatically over the past few decades, with a 46% decline in the number of U.S. companies listed on exchanges since the peak in 1996. What is driving this trend? One reason is that public companies are getting bigger and more stable. Another reason is that companies are staying private longer.

U.S. companies have accessed public market capital through initial public offerings, or IPOs, since the Dutch East India Company launched in 1602. Between 1976 and 1996, the number of listed companies rose 50%, thanks in part to the dot.com bubble of the 1990s. Their ranks halved over the next 10 years, through mergers, acquisitions and, as is presently the case with Sears, bankruptcies. Investors can also take a company private, as Elon Musk famously suggested in August that he would do with Tesla before settling with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Today there are far fewer public companies, but they are generally larger and more mature global competitors. Approximately 4,000 U.S. public companies are listed today, with an average market capitalization of $7.3 billion.1 In 1996, the average market cap was $1.8 billion (in today’s dollars).2 Public companies have grown substantially over the past 20 years by consolidating with industry peers or by acquiring smaller companies to access new technology or products. As a result, average market capitalization is now skewed significantly by the largest companies, with 140 companies exceeding $50 billion in market value. Fewer than 40 companies – the top 1% – represent 29% of total U.S. market cap.3

U.S. public companies also hold a lot more cash than they used to – about 22% of total assets at latest count, up from a little over 9% 40 years ago.4 That cash can be used to fund research and development, to expand into new markets, or to acquire smaller companies or competitors. It is also used to return capital to shareholders. Today, the total payout ratio, or the ratio of dividends plus share repurchases divided by net income, is 2.3 times what it was in 1996.5

With fewer companies in the U.S. public markets, some investors argue that we are approaching an unhealthy degree of industry concentration. Others see this concentration as the natural outcome of technological innovation and globalization, which have allowed the most productive and profitable companies to dominate the public markets. Certainly, there has been tremendous growth in the private equity industry. Only 24 private equity firms existed in 1980, and their combined deal volume totaled just slightly more than $1 billion. Today there are over 3,000 private equity firms with more than $1 billion in assets under management.6 Two of the largest private equity firms, The Carlyle Group and KKR & Co., have more than 650,000 employees within their portfolio companies, making both of them larger employers than any listed company apart from Wal-Mart.7

Private companies are also staying private for longer. In the past, emerging companies looked forward to an IPO so they could access public market capital, use shares for compensation or for mergers and acquisitions, and provide liquidity for founders and early investors. As described below, greater funding and exit options, decreasing capital investment requirements, regulatory changes, and the intangible benefits associated with remaining private are more than offsetting the attractions of a public listing. The availability of late-stage capital in particular has allowed some companies to grow and expand while staying private. Unicorns, or private companies with valuations over $1 billion, include Airbnb, SpaceX, Palantir Technologies, WeWork, Pinterest and, perhaps the most well-known, Uber.

Investors who can tolerate some illiquidity in their asset allocation may wish to participate in both the public and private markets. At Evercore Wealth Management, we recommend investors select private equity funds that have potential to earn a premium that compensates for illiquidity, and build an investment program that is diversified across strategies, vintage years, industry sectors and geographies. While investors who participate only in public equities can also benefit from the innovations of private companies, a significant amount of the valuation growth on those new technologies or products occurs prior to an IPO or acquisition.

Stephanie Hackett is a Managing Director and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. She can be contacted at [email protected].

Four Reasons Companies Are Staying Private Longer

1. Greater funding and exit options

Private companies can now obtain ample late-stage funding from private equity firms, sovereign wealth funds and mutual funds, all of which have been willing to fund billion-dollar investments into private companies. Aside from facilitating company growth, founders, employees and early investors can tap late-stage funding rounds to achieve some liquidity. Private companies can also access debt financing, which has been attractive while interest rates are at or near all-time lows. Debt financing allows companies to raise capital without diluting shares or adding new investors.

As an alternative to an IPO, a significant number of private companies are agreeing to acquisitions by strategic buyers (usually public companies). In 2017, just 15% of venture capital exits were IPOs; the remainder were the result of M&A deals. Public companies tend to have a lot of cash on their balance sheets, which can be used to acquire technologies or products.

2. Less capital required to build a company

Companies today need less capital to build and expand. For example, innovations in technology allow companies to use low-cost Cloud-based services rather than building their own networks and other infrastructure.

3. Regulatory changes

Regulatory changes enable private companies to stay private longer, while upping the costs of public listings. The JOBS Act of 2012 increased the total number of shareholders a company can have before being required to register with the SEC to 2,000, allowing private companies to take on more late-stage investors. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, designed to prevent the accounting frauds of the 1990s, imposed reporting and liability burdens on public company managers. Public companies have since had to pay fees for listing on an exchange and additional expenses associated with mandatory disclosures and regulatory requirements. They are also required to have dedicated resources for communicating with current and prospective shareholders.

4. Intangible benefits of private entities

Staying private longer allows founders to take a long-term view and to prioritize control and flexibility, allowing them to take risks, away from the spotlight. Public companies are more heavily scrutinized by investors, analysts and the media, as well as by competitors and activist investors.

1 “Looking Behind the Declining Number of Public Companies”, EY, May 2017.

2 “Looking Behind the Declining Number of Public Companies”, EY, May 2017.

3 “Looking Behind the Declining Number of Public Companies”, EY, May 2017.

4 T.W. Bates, K. M. Kahle, and R. M. Stulz, 2009, “Why Do U.S. Firms Hold So Much More Cash Than They Used To?” and Journal of Finance, 64(5), October 2009, pp. 1985-2021

5 “The Incredible Shrinking Universe of Stocks,” Credit Suisse, March 22, 2017.

6 “The Incredible Shrinking Universe of Stocks,” Credit Suisse, March 22, 2017.

7 The Carlyle Group, KKR, http://fortune.com/fortune500/list/filtered?sortBy=employees&first500.