Independent Thinking®

Staying on Course: Investing for the Next 10 Years

January 8, 2019

Ten years ago, the world was emerging from a bear market triggered by the worst financial upheaval since the Great Depression. Central banks maintained interest rates near, and sometimes even less than, 0% for several years, while purchasing trillions of dollars of debt instruments to try to rebuild confidence among investors, businesses and consumers. Then came the wildly profitable near monopolies of Google and Facebook, and the fourth decade of rapid economic expansion in China.

Today, years after the financial crisis, the U.S. economy is growing at a healthy rate while absorbing tightening monetary policies. However, most of the other developed economies appear to be faltering, as does China’s. Even now, a period of renewed stability overall, we have Britain’s troubled departure from the European Union and the unconventional Trump administration to contend with.

The best we can do to serve our clients is to continue adhering to our guiding investment principles: Invest for the long term, use an optimal amount of diversification – enough to improve returns and control risk, but not so much as to add unnecessary cost and complexity – and be aware of how the behavioral tendencies of investors, ourselves included, can influence decision making.

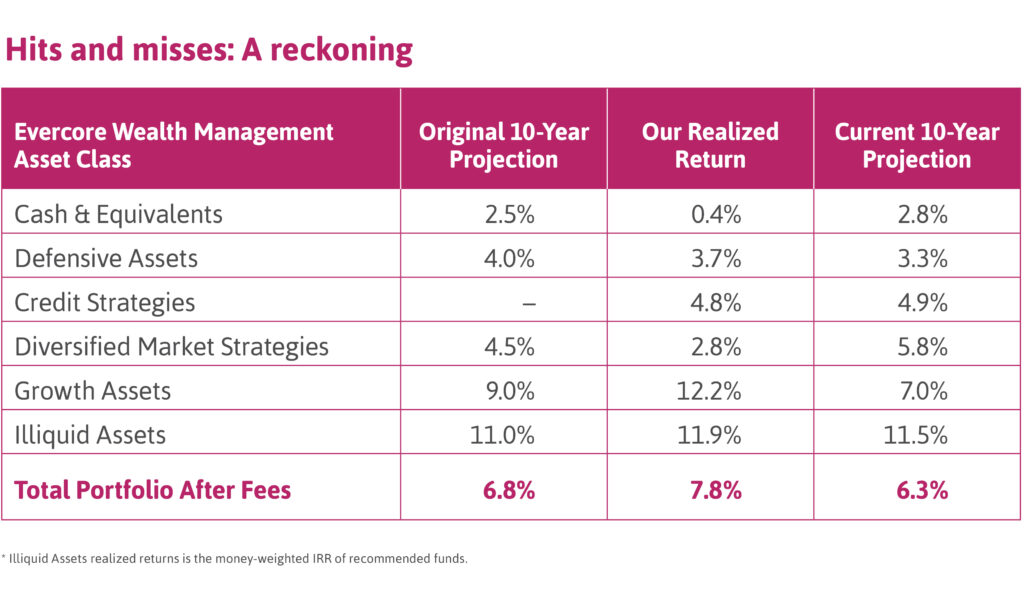

We base our investment policy on our own 10-year return and risk forecasts for major asset classes, which are shown on below with actual market returns. This has been one of the best 10-year periods on record for the U.S. stock market, even though inflation-adjusted economic growth has been a meager 2% annually. The bond market returned close to the original yield to maturity built into prices at the beginning of the period, although yields and prices fluctuated greatly. The yield on the 10-year Treasury, 2.55% 10 years ago, was 2.7% by the end of 2018, but traded between 3.8% and 1.45% during the period. Gold and oil prices both rose about 40% cumulatively, but it was a wild ride along the way.

No other major asset class came close to the returns of American stocks. The S&P 500 rose at an annualized average rate of 13.2%, while international developed market returned about half of that at 6.3%, and emerging markets did only slightly better at 8%. The average private equity fund returned 10.8% annualized, which is a comparatively disappointing return, given the limited liquidity and therefore greater risk. This offers strong evidence that investors must invest in a top-quartile fund to improve their chances of achieving an adequate return. Hedge funds have been disappointing, as well. The annualized average return was 5.2%, with equity long/short funds returning 6.1% on annualized average. Most equity long/short funds justify their high fees by claiming they can achieve S&P 500 returns with half the risk by being about 60% net long, but in the last 10 years the average fund has not even returned 60% of the market return. (Note: We don’t own any hedge funds per se, but our Diversified Market Strategies, or DMS, asset class comprises hedge fund strategies in mutual fund form and their results have been disappointing.)

The table shown above also answers several key questions: What were our expectations at the beginning, 10 years ago? How did we do? And what are our expectations for the next 10 years? As you can see, we did pretty well. Our big miss on the downside was cash equivalence; we did not anticipate that the Federal Reserve would keep short-term interest rates at 0% for eight years. Our big miss on the upside was not fully anticipating one of the great bull markets in stocks of all time. The very low short-term interest rates also help explain why defensive assets and DMS came in below expectations; in theory and practice the returns of these asset classes build on top of, and are therefore very sensitive to, the risk-free rate of return. The sustained 0% short-term rates also encouraged risk taking, which helped boost stock returns.

Our expectations for the next 10 years are similar to past experience, except we do not expect to return to 0% interest rates and we have far more modest projections for growth assets, bringing down the expected annualized return for a balanced portfolio to 6.3%. The lower forecasted returns from stocks consider the expectation that we will experience a recession sometime in the next 10 years and that economic growth will slow in the United States and most of the rest of the world as the growth rate of the population, and therefore the labor market, slows.

We are keenly watching many long-term trends, including an acceleration of innovation, the move to passive investing, growing economic inequality, the increasing conflict between the United States and China, and climate change.

John Apruzzese is the Chief Investment Officer at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Continuing the China Conversation

The cumulative total return of the S&P 500 over the last 10 years works out to 243.03%, even though real economic growth totaled only 77%. Meanwhile China’s economy grew by 122%, but the Shanghai Composite Index, a benchmark for Chinese stocks, only grew by 70.5%. It is important to note that many large U.S. corporations, including Microsoft, Apple and Nike, benefited more from China’s growth than most Chinese companies.

Last year Chinese companies sold $550 billion of goods in the United States that were made in China. U.S. companies sold close to $550 billion worth of goods and services to the Chinese, yet all but $150 billion of these were also made in China by the American companies’ subsidiaries. This harms American workers in manufacturing industries, something that President Trump has seized upon, but it works out very well for U.S. stock owners because penetrating both the Chinese labor and consumer markets greatly enhances profits and growth. This is one of the underappreciated reasons for the bitter political divide in the United States and helps to explain why the stock market is so sensitive to the ebb and flow of trade relations with China.

Another reason that the conflict with China is front and center is that a basic assumption is falling apart. Until recently there was general agreement in the West that China’s rapid development was not a serious long-term threat to the geopolitical order. Either imbalances built up in the centrally commanded pursuit of maximum growth would cause the economy to stop working eventually, according to the prevailing view, or else China would have to open up politically and progress toward liberal democracy.

Forty years on, neither development has occurred. If anything, moves toward political freedom are being reversed as new technology helps the state control the population. Meanwhile, the economy continues to grow at more than double the U.S. growth rate and the country remains on track to overtake the United States as the world’s leading economy. – JA