Independent Thinking®

What’s Up with Negative Interest Rates?

December 17, 2019

The first of what modern investors would recognize as government bonds were issued in the 12th century by the city-state of Venice to finance continual wars with the Byzantine Empire and rival Italian city-states. All Venetian citizens were required to finance these wars by purchasing the bonds, called prestiti, but accounts of the era suggest the public didn’t object; the promise of an annual return of 5%, with variable interest rates introduced a couple of centuries later, was thought to be better than being taxed directly and receiving no return at all.

The prestiti contributed to the war effort, and they also helped to establish the foundations of modern finance by explicitly conveying the idea that money has a price: the interest rate.

Centuries later, we might think the Venetians drove a hard bargain with their rulers. We pay taxes to our governments and still lend them money, too, and for returns far less than 5%. Since the global financial crisis, in fact, interest rates on government debt issued in mature economies have been close to zero, or even less than zero in many places, forcing bond investors to pay for the privilege of lending money.

Bonds with negative yields accounted for as much as $17 trillion in 2019, or about 25% of the global sovereign debt, although a recent uptick in rates has pushed the figure down to around $12 trillion. Bonds are being issued with negative yields in Japan and throughout Europe, even in Greece, which only emerged from an international bailout program in 2018, yet was able to issue three-month debt priced to yield -0.02% in October.

Who would buy assets with such miserly yields, and why? And could we ever have bonds with negative yields here in the United States?

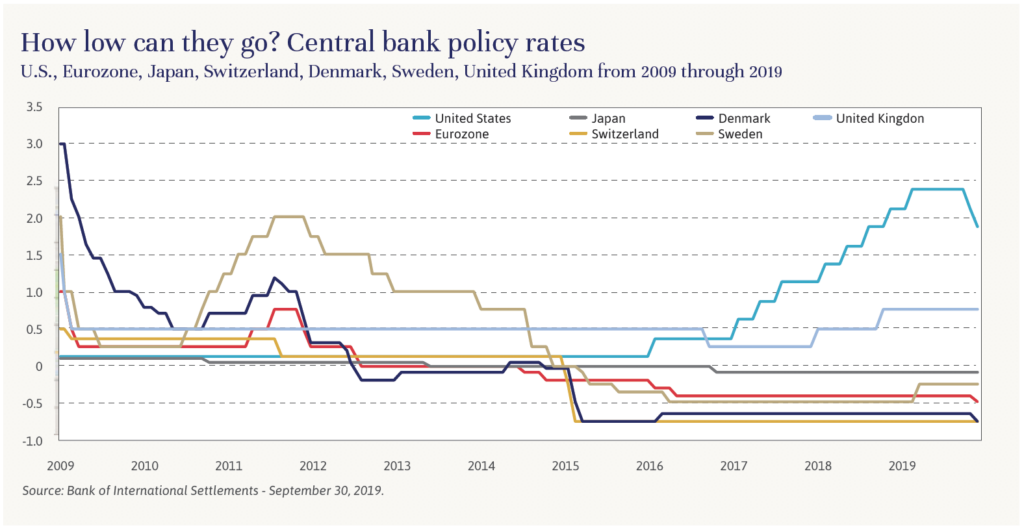

Negative interest rates exist largely because central banks want them. The Federal Reserve maintained a zero-interest rate policy, or ZIRP, earlier in the decade, then adopted a tighter stance beginning late in 2015, raising interest rates nine times, a quarter-percentage-point each, over the next three years. The Fed reversed course a few months ago, executing quarter-point cuts three times since July. Central banks in much of the rest of the developed world also dropped rates to zero percent, but then kept dropping them. Starting in Denmark in 2012, followed by the Eurozone, Japan, Switzerland and Sweden, central bankers implemented not ZIRP, but NIRP, or negative interest rate policy. The Bank of England, like the Fed, is an exception, but just barely; it has maintained its short-term policy rate at 0.25%.

The rates set by central banks are those at which commercial banks lend money to one another on overnight loans from their reserve balances, and these rates heavily influence all other interest rates within a country. The central banks’ intention in introducing negative interest rate policies was to help stimulate economic growth by making the hoarding of cash so unrewarding that it would persuade individuals and businesses – still wary of taking risks after having experienced the financial crisis so recently – to spend and invest instead.

But some investors still want to buy bonds, even with rates below 0%. How does that even work? A bond will have a negative yield when investors pay more for it than they will receive from all coupon payments and the return of principal at maturity. Here’s a straightforward example: In August, Germany issued a 10-year bund (its version of a Treasury bond) with no coupon. Buyers paid €102.64 for a bond that will be worth €100.00 when it matures, and they will receive no interest in the meantime. That works out to a return of about -0.25% annually, assuming an investor holds the bond to maturity. That bondholder, in effect, will pay ¼ percent annually to lend money to the German government.

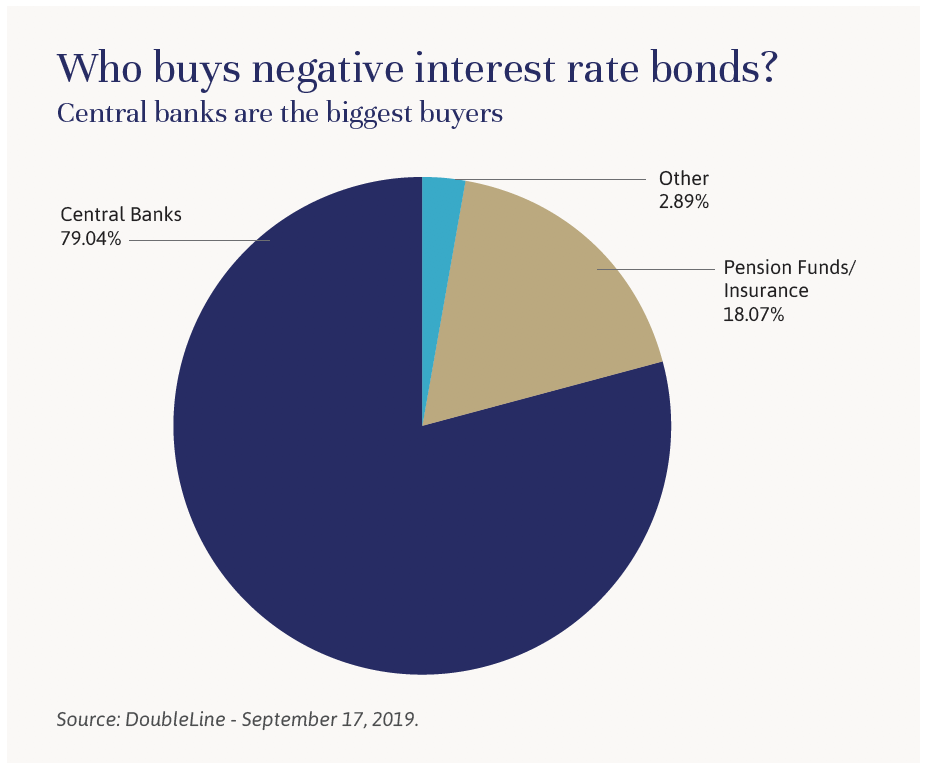

Why would anyone do that? It turns out the biggest purchasers of negative interest rate bonds are the central banks themselves, as illustrated in the chart below. This is a consequence of another unconventional policy arising from the financial crisis – quantitative easing, or QE, in which central banks buy securities to increase the money supply and encourage more risk-taking in capital markets. The U.S. stopped QE in 2014, but central banks in other large, developed economies continue the practice. As a result, about 79% of negative-yielding bonds, as of September, were held by central banks. Most of the rest (18%) were owned by entities that are controlled by governments or that need long-term assets to match long-term liabilities, such as pension funds and insurance companies. The amount of negative-yielding securities in the hands of other investors or speculators is actually quite small, at around 3%.

But 3% of $17 trillion is still a large amount to put into securities that are guaranteed to lose money if held until maturity. Investors do it for at least two reasons:

First, they may believe interest rates will continue to drop. A buyer of bonds, or bunds as in the example above, can sell them at a profit if the yield continues to fall. Whether the sign in front of the yield is positive or negative, a bond’s price moves inversely to its yield. Second, they may believe there will be deflation over the life of the bond. If a bond yields -0.3% a year over the holding period and the issuing country experiences deflation at 1%, the real (inflation-adjusted) yield will be 0.7%, increasing the bondholder’s purchasing power.

There may be a rationale for buying negative-yielding bonds, but has economic performance justified the issuance of them? Because Japan has had inflation ranging between 2% and -2%, and very low real economic growth and interest rates over the last 30 years, negative interest rate policy seemed a reasonable experiment. The Japanese economy is probably the best in which to examine the success or failure of negative interest rate policy, or NIRP.

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco recently released a paper that analyzed the early efficacy of negative rates by reviewing the impact on market-based inflation expectations. It concluded that NIRP had the opposite of its intended effect, as inflation expectations fell on announcements surrounding implementation of the policy. Meanwhile, bank profitability and investment spending in Europe and Japan has decreased in the years since NIRP was implemented. Other factors may be influencing growth in these regions, but, empirically, NIRP has not had a positive impact on banks, businesses or consumers in any of the regions where it has been tried thus far.

We believe this makes the introduction of NIRP in the United States unlikely in the near future. But there is no guarantee that if inflation and growth remained stubbornly low, the Fed wouldn’t try it.

As John Apruzzese says in his article, Powerful Protection in a Low Interest Rate Climate, we expect interest rates and inflation to remain low for the foreseeable future due to a number of factors, including an aging population, technological innovation that enhances productivity, a high debt burden, and heightened trade and competition fostered by globalization. There is a path to negative yields, but outside of the case of a deep and prolonged recession, we believe U.S. bond investors will not have to pay for the privilege of lending to our government anytime soon.

Negative rates have become a common feature on the investment landscape in the developed world. As U.S.-based investors, we view the opportunity afforded by domestic bonds in the context of what’s on offer elsewhere. Yields are low relative to what has been available over the course of history, but they are quite high relative to yields in much of the rest of the world today. For instance, as of the end of September, a 10-year Treasury bond yielded about 2.25 percentage points more than a 10-year bund. This yield advantage, along with the negative correlation factors, provides another reason why high-quality bonds should remain a part of balanced portfolios for U.S. investors.

Brian Pollak is a Partner and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].