Independent Thinking®

COVID-19 Response Diagnosis: Inflation or Deflation?

July 6, 2020

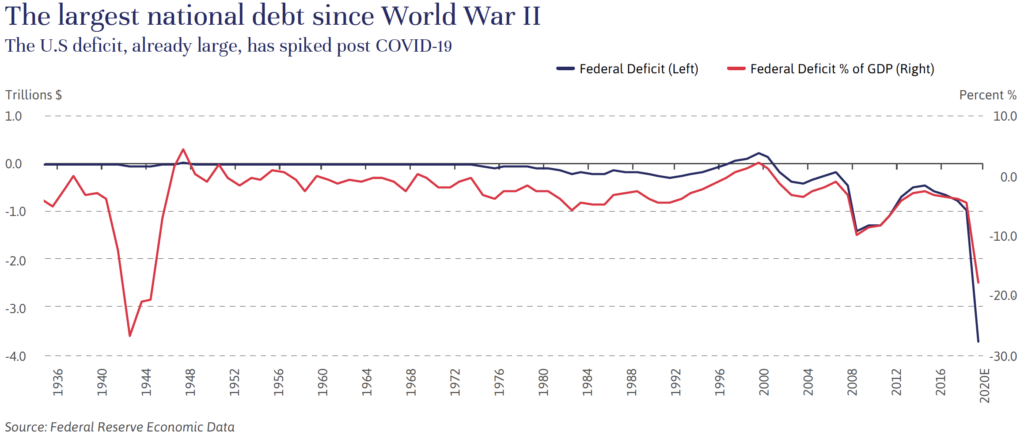

The United States is on course to amass a $3.7 trillion additional net debt for 2020, the equivalent of 17.9% of the national GDP, the largest on both accounts since WWII. The aggregate gross domestic government debt-to-GDP ratio has tripled since 2000. And the Federal Reserve is expanding its balance sheet at a record clip. But inflation, the natural consequence of fiscal and monetary easing, according to some schools of economics, is nowhere to be seen. Instead, deflation appears to be the bigger risk, at least for now.

COVID-19 fiscal relief in the United States has to date focused on providing temporary support to the employees and employers most susceptible to layoffs and closures. It has also served to stabilize the markets. Much of that support is scheduled to roll off as the economy improves. Economists are in broad agreement that this fiscal spending will address already lost production but just partially offset the expected decline in GDP since mid-March. In other words, the relief so far has been just that; relief, not a lasting stimulus.

At the same time, consumer demand and prices have plunged. While there have been some supply shocks among essentials (milk, eggs and so on), the most recent CPI year-over-year reading was 0.2%. Clearly, the capital markets are not expecting much in the way of inflation anytime soon; the five-year, five-year forward breakeven inflation rate, which measures expected average inflation over a five-year period that begins five years from today, is now just around 1.5% – and 10-year inflation, as measured by yields on Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPs, is lower still, at around 1.3%.

Of course, this deficit spending by the federal government does add significant debt to the U.S. balance sheet. However, large fiscal deficits and government debt are generally not viewed by economists as inflationary. Instead, high debt loads relative to GDP often result in disinflation or deflation, as has already happened in Japan and much of Europe. Empirical studies show that the higher the sovereign debt load becomes, the more the returns on that spending diminish. In other words, at these levels each debt-funded dollar spent creates less than a dollar of growth, which is why high debt loads relative to GDP often result in disinflation or deflation.

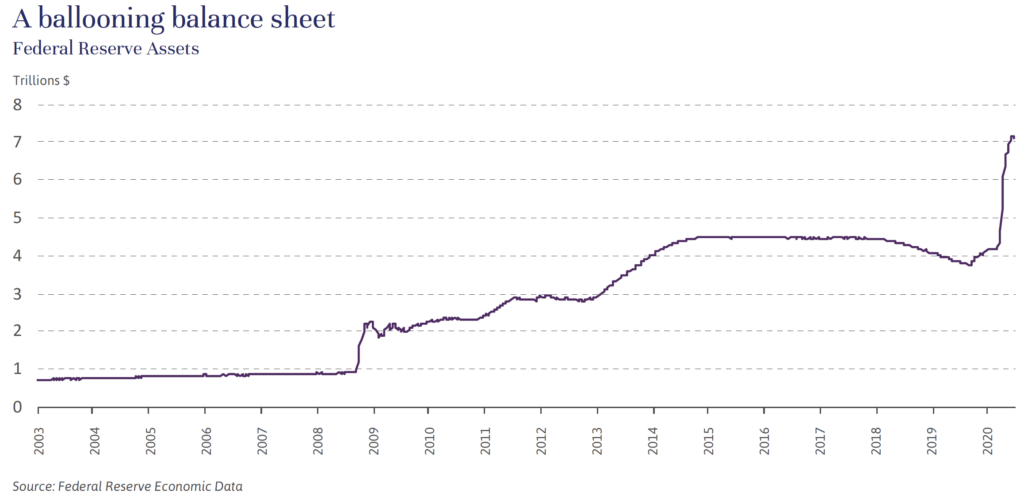

Moving to monetary policy, the Fed expanded its balance sheet considerably post the 2008-2009 financial crisis, as did other central banks, without sparking inflation. But this year’s monetary expansion has been bigger and more rapid than previous efforts to jump-start the economy. Does it therefore follow that it will be inflationary?

Perhaps it might be, if the Federal Reserve were to not just expand its balance sheet by purchasing securities temporarily – as it did with quantitative easing, or QE, post the financial crisis of 2008-2009 – but were to also extend credit to the private sector on a permanent basis, delivering this so-called helicopter money directly and permanently to the consumers and small businesses most likely to spend it. Importantly, this would involve the government and the Federal Reserve working in concert, with the Treasury issuing debts to finance the permanently elevated government deficit, and the Federal Reserve then purchasing the new debt with newly printed money.

This policy could be considered a version of the highly controversial Modern Monetary Theory, as described here, which would create the potential for high inflation. Indeed, some argue that a temporary version of this policy is in effect now, as the Fed will buy nearly all of the massive net debt issued by the Treasury in 2020. But there is not yet a broad expectation in the markets – or an explicit promise by the Fed – that this will be perpetual. That’s an important distinction, and it’s not yet evident.

We are also watching to see if other experimental monetary policies, such as negative interest rates or more permanently purchasing credit or equity assets on the central bank’s balance sheet, are deployed here in the United States – and if so, how those programs might impact inflation.

Another argument for rising inflation is the prospect of continuing deglobalization. If individual countries, concerned about the safety and controllability of their supply chains, look inward for goods production, a drop in global trade would be expected, making it more expensive for each country to produce goods, thus leading to some inflation. Sino-American relations, already problematic, could certainly deteriorate at the expense of international trade, as indeed was already the case pre-COVID-19. However, any cost or efficiency loss resulting from the altering of global supply chains would likely be temporary. We would expect that companies in the United States and other large developed markets would eventually adjust, aided by advances in technology such as 3-D printing and robotics.

In any case, these arguments for inflation remain largely speculative. As discussed in previous issues of Independent Thinking, three deflationary secular forces – high debt loads, aging demographics and technological disruption – continue to keep inflation in check. In fact, one could easily argue that all three have accelerated as a result of the current crisis. The potential for higher debt burdens on consumers, businesses and municipalities could create a cycle of private sector debt deleveraging, which in itself will be disinflationary. And the broad acceptance of and accelerated use of technology, such as teleconferencing and e-commerce, is also hastening disinflationary trends.

Low inflation was an important component of the decade-long bull market in equities and the key driver of the 30-plus year bull market in bonds. We do not view high inflation as an immediate, or even a likely, medium-term threat. Whether monetary and fiscal policies result in significant long-term inflation depends on the magnitude of deficit spending, the permanence of that spending, how much of that spending is monetized by the Fed, tax and regulatory policy, and other inflationary or deflationary forces occurring alongside those policies.

Brian Pollak is a Partner and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Deconstructing Deflation

The term deflation often has negative connotations, evoking images of a Depression-era economy. But deflation can be good or bad, depending on the drivers. At present, we see a mix of both.

Good deflation can occur as a result of improving aggregate supply from factors such as globalization and technological disruption. Resulting higher productivity and cheaper inputs shape an environment in which both consumers and producers can mutually thrive as prices, as well as costs, decline. Incomes rise and output increases. This type of deflation can coexist with real economic growth.

Bad deflation often occurs as a result of declining aggregate demand from trends such as aging demographics and high debt burdens. Declining consumption coupled with less investment produces a challenging cycle in which consumers further delay purchases and already high debt levels become even harder to pay back for companies. Unemployment rises and output detracts. This type of deflation pushes real growth lower, creating a downward spiral.