Independent Thinking®

Planning With Purpose: Non-Charitable Purpose Trusts

October 19, 2021

If we can’t take a treasured possession with us, we might want to ensure that it’s taken care of. hat’s true for all sorts of assets, whether a beloved family vacation home, an art collection, a pet, or even our own cryogenically frozen remains or other genetic material. (The verdict is still out on whether we can, in fact, take the last with us.)

A non-charitable purpose trust can serve as a steward of certain valued assets, protecting them for years to come or even in perpetuity. Once the sole province of offshore jurisdictions, the non-charitable purpose trust is now permitted in some form in almost every state.

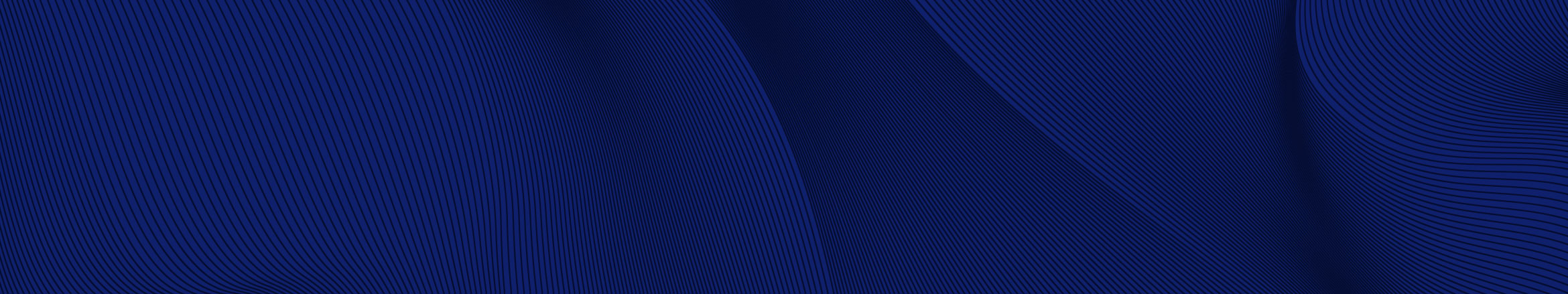

Unlike other trusts, a non-charitable purpose trust is designed to carry out a specific purpose, rather than benefit certain named beneficiaries. As illustrated by the charts below, non-charitable purpose trusts have a wide range of potential applications.*

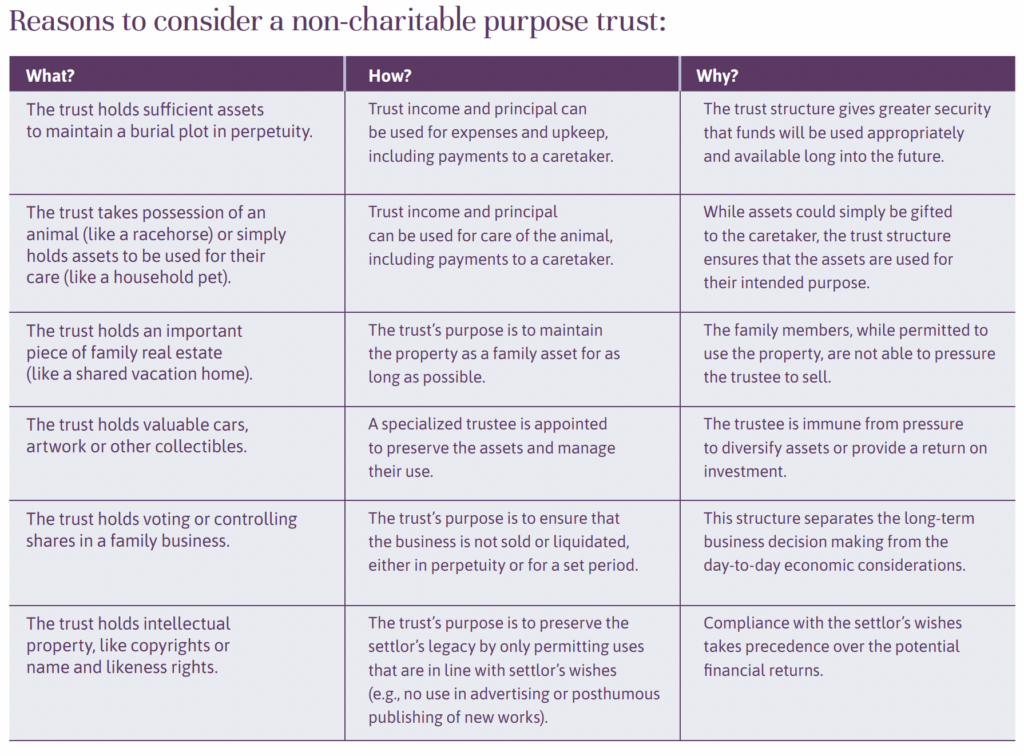

There have historically been two primary uses for non-charitable purpose trusts (which were sometimes referred to as “honorary” trusts). The first use is the care and maintenance of a burial plot. This structure could theoretically be applied to the maintenance of cryogenically frozen remains or other genetic material, but that is still up for debate. The second is the care of pets or other animals after the death of the owner. Depending on the maximum term under state law, such trusts may be structured to continue in perpetuity for the benefit of both the named animals and their future offspring.

An increasingly popular and evolving use of non-charitable purpose trusts is to hold an asset that has particular meaning or importance to the settlor. The advantage of this structure over a traditional trust is that the focus will be on the best interests of the asset itself, rather than investment performance or the wishes of individual beneficiaries. These are often described as stewardship trusts, as the primary purpose is the preservation of the asset in accordance with the settlor’s wishes and values.

All of these trusts can also be structured to distribute out to named beneficiaries, whether individuals or charities, or be held in further trust for their benefit, upon the completion of the purpose.

So, who ensures that the settlor’s wishes are carried out when there are no beneficiaries? For trusts with a traditional charitable purpose, the State Attorney General in each jurisdiction is empowered to step in; that’s not the case with non-charitable purpose trusts. Enter the “Enforcer,” who, as the title suggests, is named in the trust agreement to enforce its terms and hold the trustee accountable.

The flexibility of a non-charitable purpose trust depends largely on the state where the trust is established, meaning that choice of situs is critical. States with more traditional laws may permit non-charitable purpose trusts only in very specific circumstances; for example, the care of animals or the maintenance of gravesites as discussed above. Such states may also limit the maximum term to as little as 21 years. However, some states, including Delaware, permit trusts for any lawful purpose that is reasonable, attainable, and does not violate public policy, and these states have statutes expressly permitting such trusts to exist in perpetuity.

The longer the term of the trust, the more likely it is that there will be a material change in circumstances affecting the fulfillment of the purpose. Therefore, for a long-term or perpetual trust, it may be advisable to appoint a trust protector with broad powers to, for example, modify the purpose, add beneficiaries or terminate the trust. This strategy can be combined with directed trust statutes to further customize and allocate the powers under the trust, which is particularly beneficial if the trust holds unique assets that require specific skills to manage.

Given the specialized nature and near-limitless options for non-charitable purpose trusts, the choice of fiduciary is also a critical decision. In some instances, the best option may be to have a trusted individual serve as the decision maker with respect to the purpose, with a corporate trustee in place to handle the administrative functions (and also grant access to the preferred jurisdiction). On the other hand, the trust will likely need to hold sufficient investable assets (in addition to any “special” assets) to ensure that the purpose can be maintained for the expected term of the trust. Responsibility for such assets may be better allocated to a corporate fiduciary or professional investment manager. Fortunately, the states that permit long-term non-charitable purpose trusts also tend to have robust directed trust statutes that permit this level of customization.

As to tax, non-charitable purpose trusts are generally subject to the same tax systems as traditional trusts. However, it is important to note that, from a tax perspective, non-charitable purpose trusts have more in common with traditional irrevocable trusts than charitable trusts.

For income tax purposes, like traditional trusts, non-charitable purpose trusts can be structured as grantor trusts (income is taxed to the grantor/settlor) or non-grantor trusts (income is taxed to the trust). The grantor trust structure is the most straightforward, at least while the settlor is living, as all income simply passes through the trust and is reported on the settlor’s income tax return.

Similarly, for gift tax purposes, despite the absence of identifiable recipients, contributions to a non-charitable purpose trust are considered gifts to the same extent as contributions to a traditional trust. Thus, like traditional trusts, a non-charitable purpose trust can be structured as a completed gift or an incomplete gift. However, gifts to a non-charitable purpose trust typically will not qualify for the annual exclusion from gift tax, because there are no individual beneficiaries to possess withdrawal rights (often referred to as “Crummey Powers”). Also, unlike a charitable trust, the initial funding of the trust would not qualify for the charitable deduction.

Finally, while it may seem unlikely that a trust without beneficiaries would create any generation-skipping transfer (“GST”) tax concerns, it is important that a full GST review be performed. For example, there may be a need to allocate GST exemption to the trust if there is a possibility that the assets will pass to grandchildren or to more remote descendants once the purpose has been completed.

A non-charitable purpose trust is a unique estate planning structure that may not be appropriate for everyone. However, for those with a need to care for animals or to preserve unique assets, or to further causes that do not fit into the traditional charitable trust mold, they present a powerful and flexible tool. While the focus of traditional estate planning tends to be on tax savings, asset growth, and efficient transfers of wealth, the non-charitable purpose trust is focused on ensuring that one’s wishes are carried out, taking into account one’s values and priorities, without diminution by economic or beneficiary concerns. In this regard, they should be considered a valuable complement to the more traditional estate planning structures.

Alex Lyden-Horn is a Managing Director and Director of Delaware Trust Services and Trust Counsel at Evercore Trust Company, N.A. He can be contacted at [email protected].

* Another broad category of uses for non-charitable purpose trusts is the furtherance of specific public policies or quasi-charitable purposes that would not otherwise meet the requirements for a traditional charitable trust, which offers a management vehicle for philanthropic gifting without the restrictions that accompany a purely charitable trust, but forgoes the usual charitable deductions associated with creating a charitable trust. A full discussion of this structure is beyond the scope of this article.