Independent Thinking®

Echoes of the Past in a New Economy

March 3, 2022

History, said (maybe) Mark Twain, doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes. Investors may hear echoes of the past in the events unfolding in the Ukraine and in the rising tension between China and the United States, but it would be a mistake to draw narrow parallels. That’s true too for this and earlier periods of inflation.

The Consumer Price Index, or CPI, is 7.5%, its highest rate in 40 years, a shocking change after two decades at under two percent. And potentially sustained higher prices for global commodities, notably oil and wheat, in the wake of the Russian invasion of the Ukraine, won’t help. Some observers are understandably anxious that this could signal the start of another period like 1973-1981, when inflation averaged about 9.25% and real GDP growth was modest, a combination known as stagflation. But today’s situation is different on three major counts: productivity, demographics, and the relationships between wages and prices.

PRODUCTIVITY

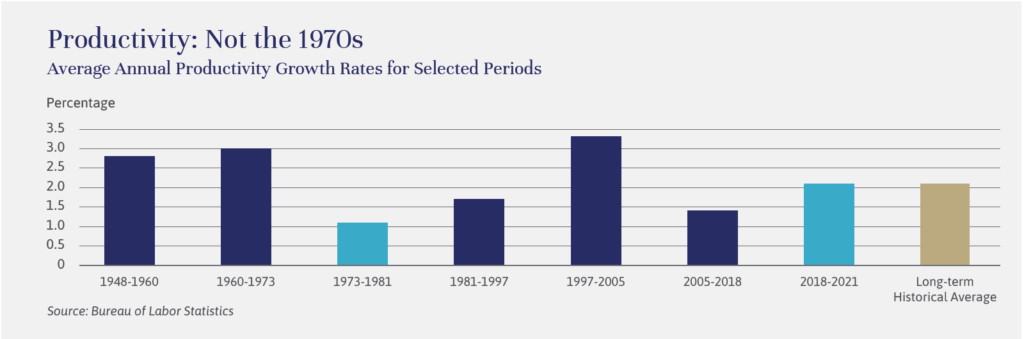

The nine years starting in 1973 marked the lowest productivity rates post-WWII, generating just 1.1% labor force productivity growth, or half the rate for the full period, as illustrated in the chart below.

Today, there are reasons to think that the recent uptick in productivity in the last two years could usher in a period of still higher (above 2%) productivity growth. In addition, capital spending (CapEx) is robust, with expenditures increasingly focused on technological advancements and significant productivity-enhancing technology. We can see this through the growth in robotic installations across all industries, which has been steadily growing in the last decade, and the percentage of overall CapEx that is focused on new technology. While we may not see a 50s-, 60s- or late 90s-style productivity boom, recent CapEx trends and technological advancements should drive productivity to at least the long-term average of above two percent. Strong productivity growth perhaps makes the best case for why stagflation is less likely moving forward.

DEMOGRAPHICS

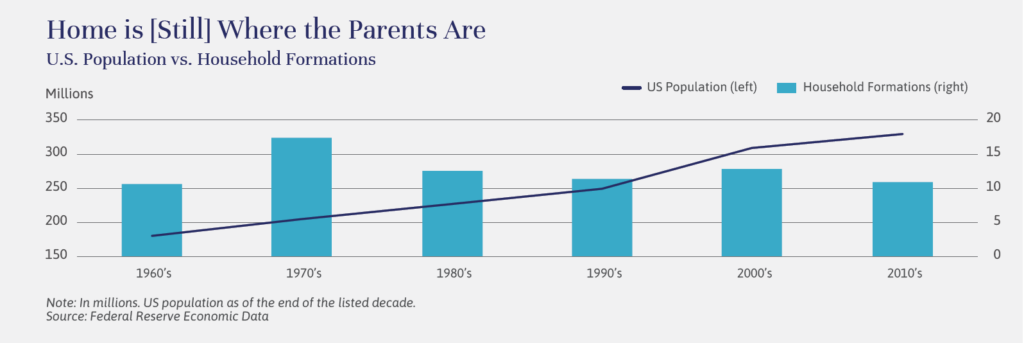

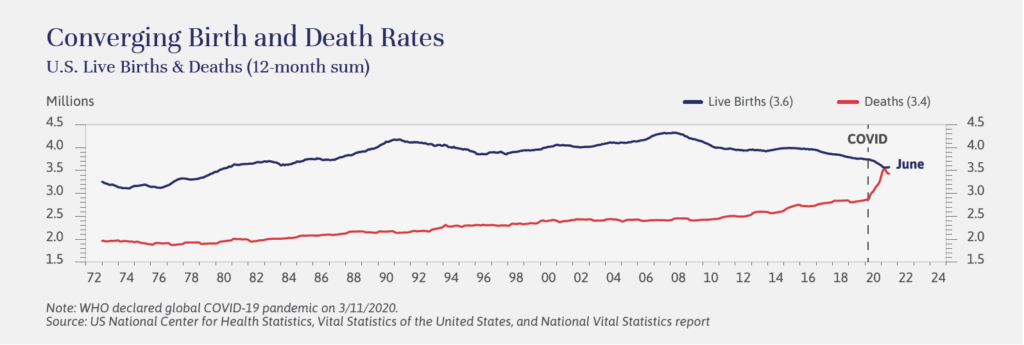

While the Millennial generation is almost as large as that of their Baby Boomer parents, they aren’t forming households and having babies at anything like the same rate. Indeed, there were nearly seven million fewer households formed in the decade of the 2010s than in the decade of the 1970s, despite a population base that was nearly 40% smaller. With fewer new households being formed, it is no wonder that the number of births and deaths in 2021 was roughly the same. COVID-19 contributed to the deaths, but the low birth rate did far more to change the equation. (See the chart below.) With birth rates so low, U.S. population growth will depend solely on net immigration, a trend that has also recently been moving in a negative direction.

At the same time, Baby Boomers are retiring at a high rate (the youngest Boomers are now in their late 50s). As retirees generally consume less than those in the labor force, and households with babies generally consume more than those without children, it seems that downward pressure on demand will serve to also dampen inflation for some time to come. It’s also worth noting that even though Boomers are retiring, the average age of the labor force continues to increase, another potential argument for long-term high productivity and low inflation.

WAGE-PRICE SPIRAL

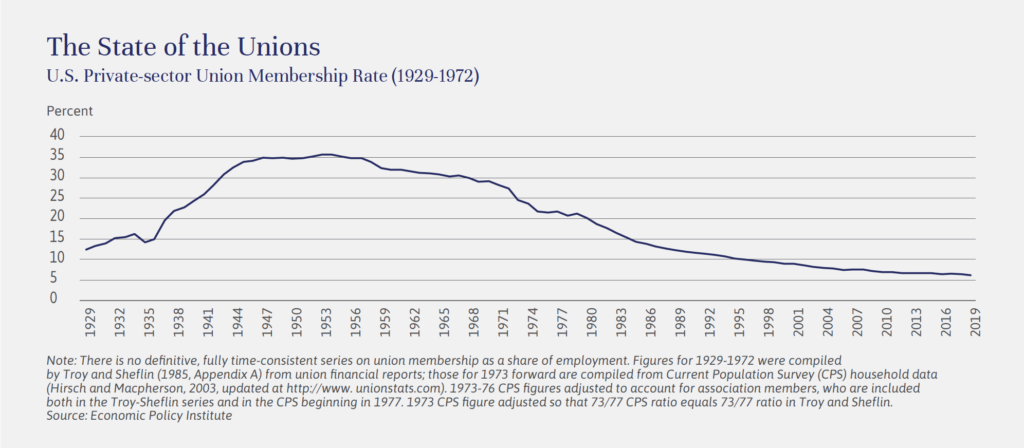

In the 1970s, unionization was broad-based in the private sector, representing between 25%-30% of the private sector work force through most of the decade – down from its peak in the 1950s but a powerful force nonetheless, as illustrated below. Many of the unionized private sector labor contracts in the 1970s (as high as 59% in 1970) were subject to cost-of living adjustments, or COLAs, meaning that many union wages were tied directly to inflation. A manufacturer of the day, having its primary expense (labor) tied directly to inflation, and with little advancement in productivity to offset those higher costs, would have no choice but to increase the price of products to keep margins at least somewhat intact. Higher prices passed through to the consumer would again impact the calculated rate of inflation in the labor contracts, causing further wage increases.

Today, with only 6% of the private sector labor force unionized, and a very small percentage of that group with wages tied to COLAs, a 70s style wage-price spiral is quite unlikely, even if wages continue to rise.

During the 1970s, Baby Boomers were pouring into the labor force, causing an oversupply of labor, which theoretically should have driven the price of labor down. But because of the combination of high unionization rates and high rates of COLAs in collective bargaining agreements, labor costs continued to rise. The abundant supply of workers also made it easy for corporations to hire new workers as needed, and corporations in aggregate did not make significant technology-driven capital investment to reduce their labor costs and improve productivity.

Today, there is a real labor supply problem. In 2021, wages rose 5.7%, with lower-wage workers experiencing a higher wage increase than higher-wage workers. Although they did not quite keep up with the high rate of inflation, further increases are expected in 2022. Can corporate margins keep pace with these wage increases? As John Apruzzese discusses in his article, Powering Up: Technology Continues to Drive the Markets, productivity will determine the answer. If wages increase by 4% and productivity increases by 2%, the unit labor costs will be increasing by 2%, a manageable scenario for most companies and a healthy increase in wages for most employees.

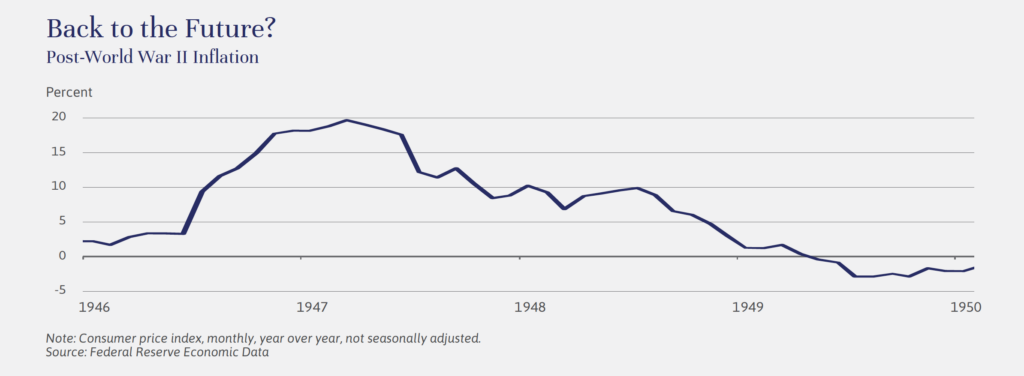

While there are many other factors that could impact the economy and the inflation backdrop, and we are certainly maintaining vigilance in portfolios to protect against worst-case outcomes, we don’t think the current period will repeat, or even rhyme with, the 1970s. Perhaps the post-World War II bout of inflation, between 1946 and 1948, is more analogous. Then, as now, there was significant suppressed demand and supply chain disruptions, and then a sudden spike in consumer demand, which caused inflation to surge to 20% in July 1947. Inflation, as illustrated below, then quickly dissipated, and a period of disinflation set in.

We are living in interesting times, with echoes of the past but also important new influences. For now, we are comfortable with our current asset allocation and remain confident in the continued strength of corporate earnings and real GDP growth. We will be watching for potential new risks and opportunities, including in Europe, where we all hope for better days soon.

Brian Pollak is a Partner and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].