Independent Thinking®

A Formula for Maximizing Gift Exemptions

March 3, 2022

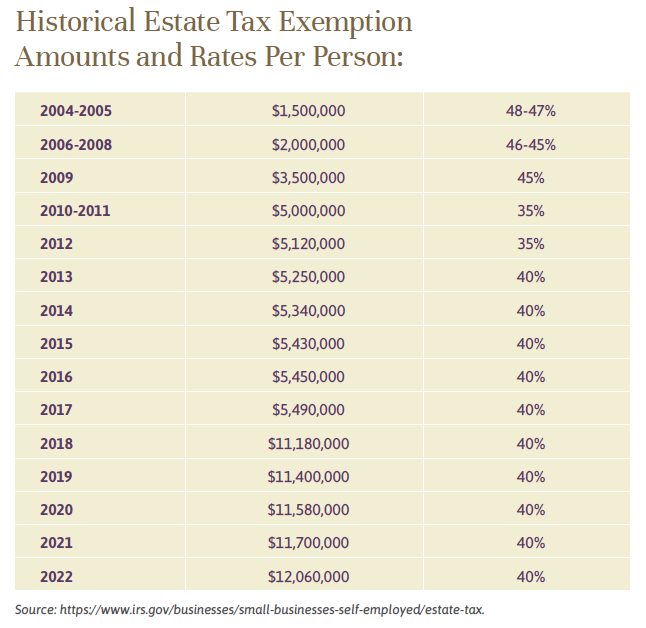

In the absence – yet – of new tax legislation, families face continued uncertainty regarding the future of the estate and gift tax systems. Washington could remain in deadlock on this issue, of course, but tax changes could also be back on the agenda soon, along with the possibility that they could be made retroactive to the beginning of the year. As it is, the current inflation-adjusted exemption of $12.06 million is set to recede to about $6.5 million in 2026.

That’s no reason to rush in, of course. Significant wealth transfer should always be informed by substantive discussions among family members, and with the family’s wealth and fiduciary advisors and other trusted members of their team. As Jeff Maurer writes in his article, Now What? Time to Revisit Goals, the starting point should be a thorough analysis of whether the donors can maintain their lifestyle after the gift is made. But for families who have done the planning work and are prepared to make gifts, there may be several non-tax benefits to be gained by gifting sooner rather than later (or not at all).

First, gifting now removes future appreciation from the estate. Second, it provides current creditor protection. Third, it may enable the estate to avoid state estate or inheritance taxes on the gifted assets.

As for the tax advantages, there is a considerable incentive to give as much, if not all, of the current exemption amount in this environment. Look at it this way: If you were to make a gift that used $5 million of the current $12.06 million exemption, and the exemption were to be reduced to $6 million, your remaining exemption at that time would be $1 million, putting you in no better place than if you had waited. If you used the full current exemption, the amount over $6 million and less than $12.06 million would not be subject to any clawback gift tax or estate taxation on your death if the exemption were later reduced.

There are also risks. One danger with gifting the entire exemption amount is that it leaves little margin of error should the IRS adjust the value of the gift – any increase in the valuation will be subject to an immediate 40% gift tax.

An IRS adjustment is generally not an issue with easy-to-value assets, such as cash, marketable securities, or U.S. treasuries; there are very clear valuation guidelines for those assets (for example, publicly traded securities are simply valued at the average of opening and closing values on date of gift), which leaves little room for an IRS challenge.

Assets without a readily available market price must comply with the amorphous “willing buyer and willing seller” test. Even with a comprehensive appraisal performed by an experienced appraiser, there is always a risk that the IRS will challenge the valuation, particularly if discounts for lack of marketability or control are being used. Also, if the gift fully utilizes the exemption, then the IRS has the added incentive of an immediate payday if it is successful in challenging the valuation.

The easiest solution to the problem of revaluation would be to gift only easy-to-value liquid assets. However, transferring closely held businesses, real estate or art often provides the best opportunities for valuations that allow the donor to take advantage of common discount techniques and also allow liquid assets to be earmarked for living expenses.

The best way to deal with this dilemma is to use the “defined value” or “formula” gift approach, which allows the taxpayer to maximize usage of the available exemption while providing safeguards against revaluation. Formulas have been commonplace in estate planning documents for as long as there has been an estate tax exemption; for example, to calculate the proper funding of marital and credit shelter trusts. Historically, courts placed strict limitations on the formula approach for gifting that limited its utility. That started changing about 10 years ago, when a series of court cases upheld the use of defined value clauses and laid a framework for their successful use. It’s important to note that, while this approach has become more commonplace, it may still be subject to IRS scrutiny.

There are two primary approaches to formula gifting. The first, more conservative approach is to direct any excess valuation to a beneficiary that would not trigger gift tax. The safest option would be a charitable beneficiary, as that strategy has been approved by the courts and is supported by the general public policy toward charitable giving. However, if donors don’t have the requisite charitable intent and a specific charity in mind, then this approach may generate less in benefits than simply paying the gift tax. In the absence of a specific charitable intent, another option would be to have the excess pass to a marital trust or an incomplete gift trust. That strategy has not been fully tested by the courts.

The second, more aggressive approach simply ties the transferred percentage of the gifted assets to the dollar value of such interest as finally determined for gift tax purposes. This is considered somewhat aggressive because the IRS chose not to acquiesce to the court decisions approving this structure. Still, it is the most efficient approach, as it does not require use of an alternate for any excess valuation, meaning that the assets go exactly where you want them to go, with no waste.

In either case, it is important that the gift instrument clearly articulates the specific intent and ties the value of the gift directly to the value “as finally determined for gift tax purposes.” An IRS revaluation for gift tax purposes does not automatically trigger an adjustment under the gift documents if that specific language is not included. It is also important that the characterization of the gift as representing a dollar value rather than a percentage of interest be carried through to the description of the gift in the gift tax return so that there is no ambiguity.

In the current environment of historically high estate and gift tax exemptions combined with the constant threat of dramatic reductions thereto, there is strong incentive to make gifts as close as possible to the current maximum exemption amount. While cash and marketable securities can be gifted in definite dollar amounts, gifts of hard-to-value assets carry the risk that the IRS will seek to revalue those assets, potentially triggering a gift tax liability. In this regard, the “defined value” or “formula” gifting approach offers an interesting mechanism to maximize the use of the current exemption amount while providing a hedge against IRS valuation challenges.

Alex Lyden-Horn is a Managing Director and Director of Delaware Trust Services and Trust Counsel at Evercore Trust Company, N.A. He can be contacted at [email protected].