Independent Thinking®

Dollar Exchange Rates: Too Much of a Good Thing?

November 28, 2022

A perspective on purchasing power parity

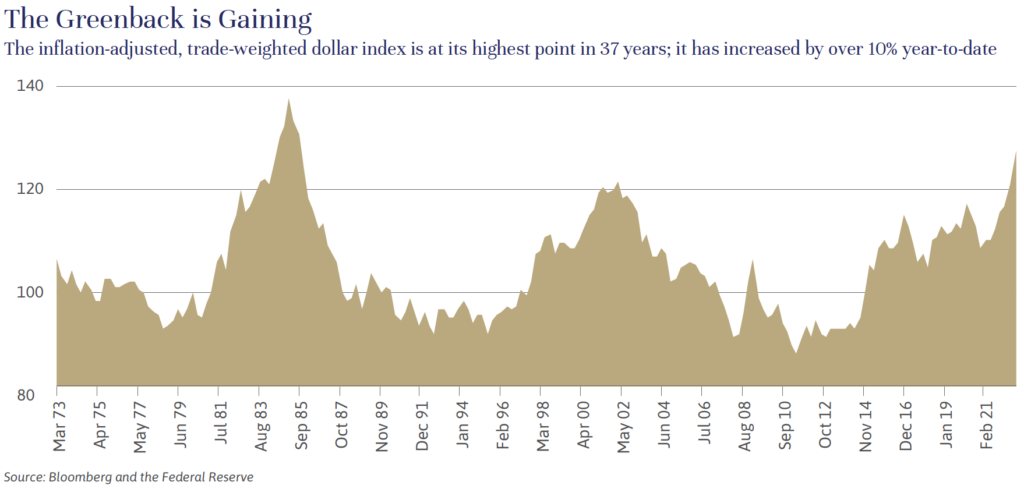

Purchasing power parity, which is calculated by measuring the price of a specific basket of goods to compare the absolute purchasing power of one currency to another, indicates that the U.S. currency is at a 37-year high. Relatively aggressive monetary tightening in the United States and increased global geopolitical risks are prompting investors worldwide to buy dollars.

The U.S. dollar hasn’t been this strong since 1985, right before representatives from West Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Japan, and the United States met at the Plaza Hotel in New York City with the shared goal of driving the dollar down, to improve the global trade balance. That degree of collaboration this time around seems unlikely and, as yet, unwarranted, but investors everywhere might have reason to hope that the dollar loses at least a little steam.

Just how strong is the greenback? It’s up by approximately 12% against the euro, 15% against sterling, and 20% against the yen from the beginning of the year through early November. All told, it’s gained more than 10% over the same period on a trade-weighted basket of other currencies, measured by the U.S. Fed Trade Weighted Real Broad Dollar index and illustrated below. That’s largely because the Federal Reserve started hiking interest rates to combat inflation earlier and more aggressively than many other central banks. While other central banks, including the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, are now raising rates, they don’t appear willing to go the same distance.

There are other factors driving the dollar’s strength. As it’s perceived by investors around the world as a safe-haven currency, the dollar typically rises during periods of economic weakness or on geopolitical shocks – and we’ve had no shortage of those over the past year. The dollar soared after the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, and the gains have accelerated since.

Of course, a strong dollar has its benefits, as Americans opting for the Hôtel Plaza Athénée in Paris over The Plaza in New York this holiday season can testify. And back at home, U.S. consumers and companies are saving on imported goods and services. But it’s bad news for our trading partners, for most emerging markets, and, ultimately, for Wall Street.

Around 40% of global transactions are in U.S. dollars, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), notably in agriculture and energy commodities. This makes it, as John Connally, Richard Nixon’s Treasury Secretary, bluntly put it back in 1971, “our currency, but [Europe’s] problem.”

Liquid fuels, which are priced in dollars, have risen by 79% in euro terms year over year through September 30, 2022, substantially more than the 58% rise recorded over the same period in the United States. Interestingly, countries with their own agricultural and energy sources, such as Mexico and Brazil, have seen their currencies hold their value. But those who are not self-sufficient are struggling. That’s particularly true for countries with high U.S. dollar debt burdens, as they are having to pay back coupons and principal using their depreciated local currency, causing their deficits to balloon when they can least afford it.

Indeed, some economists are starting to worry that this crucible of inflation and debt could force a credit crisis. Speculation that Japan has recently sold a small bit of its over $1.2 trillion in U.S. Treasuries to support its currency suggests that central bankers may be thinking the same thing. However, trouble in a smaller, still developing market, such as Colombia or Argentina, seems to us more likely, with correspondingly smaller knock-on effects.

A big risk to U.S. investors of continued dollar strength is in the stock market. Although the United States is a net importer, between 30%-40% of the market-weighted sales of S&P 500 companies are international. A strong dollar has a direct negative impact on these companies’ revenue and earnings and therefore is likely to show up in the earnings of the broader market. While difficult to isolate, some analysts estimate a 2%-3% negative impact to earnings over the course of the year based on present foreign exchange rates.

Further out, a natural catalyst for a correction in the dollar’s value would be the resumption of strong global growth alongside lower inflation, which would allow the interest rate differential between counties to close. But the IMF expects global growth to slow to 2.7% in 2023, down from a projected 3.2% for 2022 and 6% for 2021. Meanwhile, inflation is expected to decline to a still too high 6.5% in 2023, down from 8.8% projected for 2022. Full normalization may be some time off.

What if more intervention is needed in the interim? While we don’t expect that at present, it’s certainly worth considering. Would we see collaboration again on along the lines of the Plaza Accord or, more recently, during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-2009 and in the early days of the pandemic? It’s hard to say; China is marching to its own beat and the Group of 7 reaffirmed its commitment to non-intervention in currency markets just a few months ago. We have to hope that we would once again see willing and competent coordination if and when it’s needed.

Brian Pollak is a Partner and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].