Independent Thinking®

A Credit History, Built on Trust and Innovation

March 17, 2023

Since ancient Mesopotamian farmers borrowed seeds with the promise to share their crop to pay off their debts, credit has supported economic growth. Trust, which is the Latin meaning of the root word cred, is the foundation of lending. The greater that conviction, the better the terms for the borrower. But, as we’ve come to appreciate through the centuries, the greater the risk, the greater the potential investment return for the lender.

Global credit markets now represent approximately $40 trillion in capital, spanning corporations, municipalities, real estate, autos, and unsecured consumer credit, across both liquid markets and private, illiquid markets.1 While we invest the defensive portion of balanced portfolios predominantly in high-quality, investment grade municipal, corporate and Treasury securities (as these securities tend to rise when the economy and equity prices are weak), this higher interest rate environment provides additional opportunities in credit-sensitive investments.

The best-known credit sector is probably the corporate bond market, which got going when the Dutch East India Company borrowed money to finance trade routes in the 1600s. It grew over the subsequent centuries, focused on lending money at low yields primarily to the largest, best capitalized companies, with the strongest balance sheets and lowest risk of default.

This market took on a whole new life in the mid-1980s when investment banker Michael Milken of Drexel Burnham Lambert helped finance companies issuing what became known as “junk bonds” or high-yield bonds. These were bonds issued by companies considered by the market to be risky, usually due to a highly leveraged balance sheet or an uncertain business model. Suddenly, lending to low credit-quality companies at high yields took off, not just financing private equity leveraged buyouts, or LBOs (Milken’s specialty), but allowing corporations of all sizes and shapes access to relatively inexpensive and available financing.

While the trajectory has not been a straight line, facing various difficulties in the savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s and, later, the Great Financial Crisis, the high-yield bond market continued to democratize the credit markets, providing capital to more and more issuers. While Milken himself is a controversial figure, most economists agree that the advent of more accessible capital to higher risk corporate borrowers has been a tremendous boon for economic growth and innovation over the last four decades. Amazon, Netflix, and Tesla are just some of the companies that were able to access capital at challenging moments in their respective histories.

Today, the global liquid corporate high-yield bond and loan market includes 2,000 issuers and represents over $3 trillion in market capitalization.2

The securitized bond market rivals the size of the corporate bond market globally. Securitization is the process of taking certain types of assets, typically loans, and pooling those loans so they may be repackaged as marketable securities, in which the interest and principal payments are passed through to the purchaser of the new security. While investment history buffs can trace its origins to farm railroad mortgage bonds from the 1860s, the modern era of securitization began in the early 1970s. That’s when government agencies, starting with Federal National Mortgage Association, better known as Fannie Mae, began issuing residential mortgage-backed securities, allowing capital to flow to where it was previously lacking, including low-cost or affordable housing. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 further empowered issuers with greater flexibility to structure bonds with varying maturity and risk profiles.

The securitized markets then expanded to assets far beyond residential mortgages, including mortgages secured by commercial real estate properties and automobiles, and various unsecured consumer credit, including student loans and credit cards. Immense growth came at the expense of quality underwriting, however, and the securitized market came to a grinding halt in 2007. But underwriting and lending standards have since improved significantly, and the industry is now on solid footing, and continues to provide more and more avenues for small businesses and consumers to access debt capital.

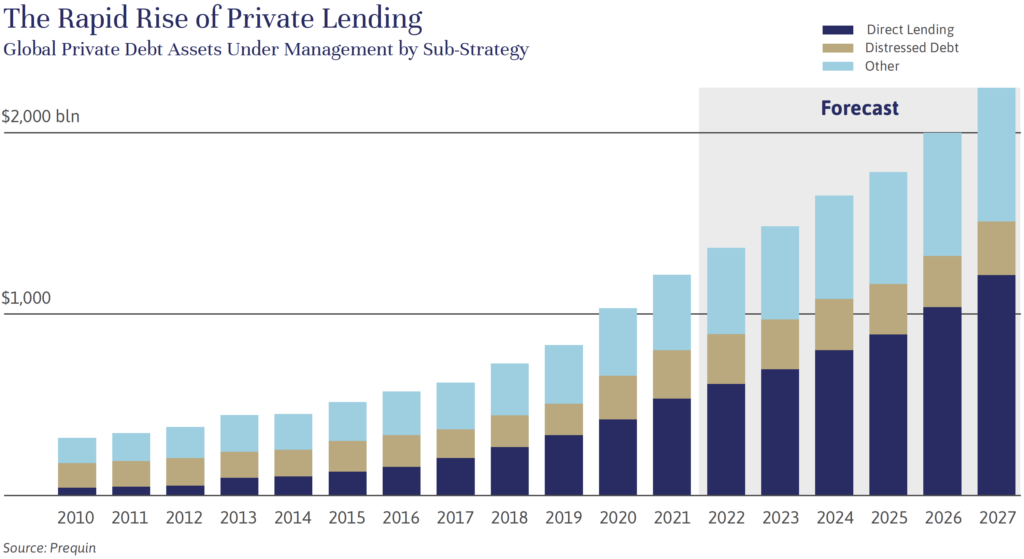

Private credit markets, which contain loans that are either smaller or more complex than those available in public markets, have also grown exponentially since the financial crisis. Private lenders today provide capital to the over 15,000 small or middle market companies that are not traded publicly.3 Global private debt has a total market capitalization of over $1.4 trillion, up from $250 billion in 2010, as illustrated by the chart below. This rapid growth in private lending has provided capital to an increasingly diverse set of companies, by expanding access beyond local bank lending offices to the often more robust and creative private capital market lenders, helping the companies to grow, hire, and combine. Please see the interview with David Golub, one of our longtime external managers, focused on middle market lending.

We’ve come a long way from seed-based loans (although it’s interesting to note that credit still underpins the global food supply). The credit market, both private and public, has weaved its way into once idiosyncratic areas, creating risk-adjusted opportunities that the Dutch East India Company and Mesopotamian lenders might have marveled at – including in high-yield corporate bonds, securitized bonds, and various investments in private credit. All of these look more appealing now after a brutal 2022, in which most credit-sensitive investments saw prices fall and yields increase – for instance, the Barclay’s U.S. Corporate High Yield Index fell by over 11%, and yields increased to over 8% from just over 4%. It will be interesting to see how credit lending continues to evolve. At present, diversified credit investments with appealing risk-adjusted return profiles, in the public markets and, where appropriate, private markets, seem to us a reasonable component of our fixed income portfolio asset allocation, in addition to Treasuries, and corporate and municipal bonds.

Brian Pollak is a Partner and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].

1 International Capital Market Association, Bloomberg

2 JP Morgan, Bank of America, 03/01/2023

3 World Economic Forum