Independent Thinking®

All the Debt in China

December 5, 2023

If misery loves company, Americans should take comfort in knowing that other countries have similarly high debt burdens. Government debt in the United Kingdom and many European Union member states hovers around the U.S. levels, and Japan’s debt represents more than twice the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). But the real standout is China, because its debt – government, corporate, and household – has grown so fast and is based on such shaky collateral.

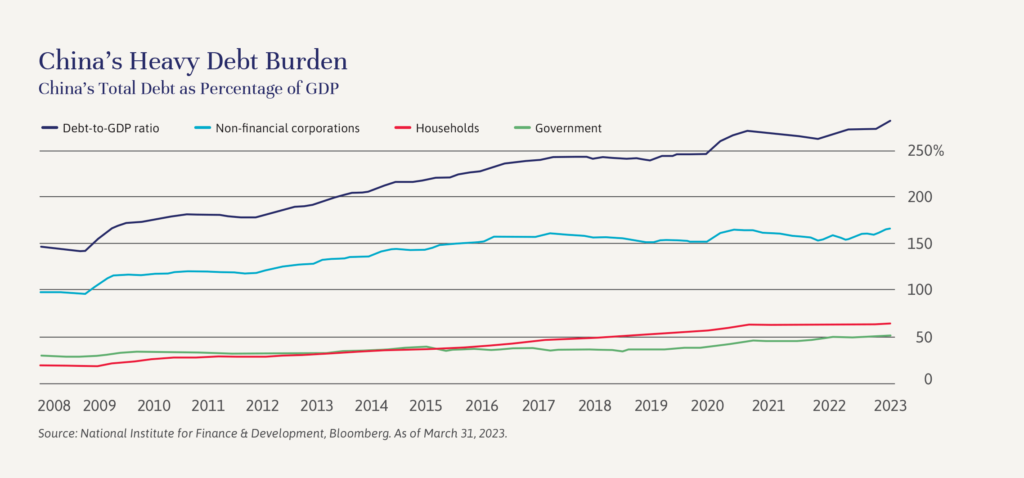

China’s debt – including government, corporate, and household borrowing – appears to have doubled in the 15 years since the financial crisis, to around 280% of GDP, as illustrated below. All three components have risen, in contrast to the United States, where corporate and consumer debt have remained relatively stable. And China’s government debt is bigger than it looks, because a large proportion of Chinese debt liabilities are really the responsibility of the government. This debt exists in the form of the approximately $9 trillion of outstanding debt obligations issued by local government financing vehicles, or LGFVs. These shadow debt structures, which are not represented in the government’s debt figures, are backed by land, infrastructure and, ultimately, obligations of local governments. Collectively, they now represent about half of Chinese GDP, bringing the total government debt close to 100%.

It has become clear that many of these projects don’t have the cash flow to support their debt loads. In some cases, they never did. In others, cash flows were predicated on property sales, but when demand for property and, consequently, property prices, dried up, so did the cash flow to pay back the bondholders. Indeed, S&P calculates that it’s possible that up to two-thirds of the real estate sector may be suffering from liquidity stress. Private real estate debt markets have also had significant struggles. China Evergrande, the world’s biggest property developer, and Country Garden, another massive Chinese home builder, have both defaulted and together have in excess of a $500 billion debt load. This has only added to the pressure on the broader property market, and as prices have spiraled downward, the dangers of a highly leveraged, property-focused economy are becoming more apparent.

The central government has stepped in for now, with a plan announced in August 2023 that allows local governments to raise about $140 billion in bond sales to refinance the struggling LGFVs. While this amount will in no way cover all the failing LGFVs, the now more explicit backing of the central government may provide some comfort to investors and banks with exposure to these vehicles. It also makes it clearer that the large debt load represented by the LGFVs can be considered a direct liability of the government.

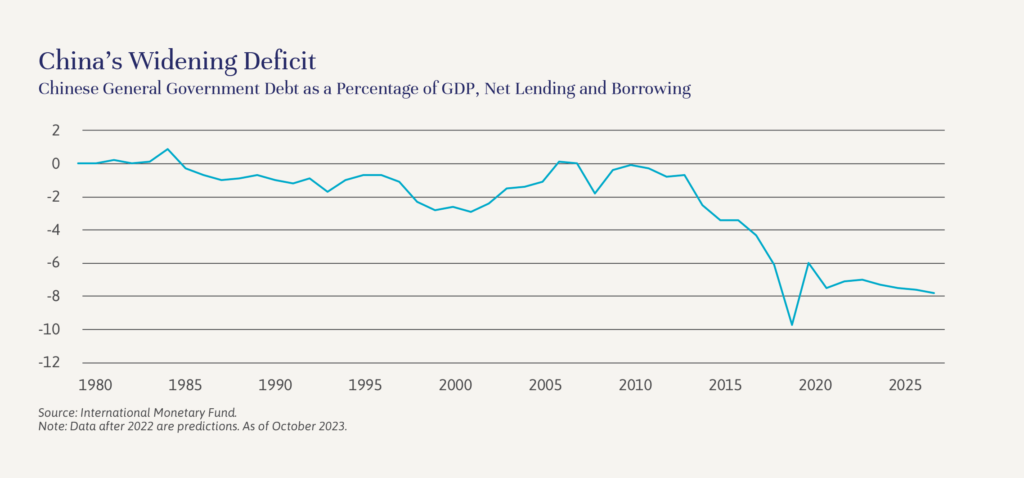

It’s understandable that China took on this debt. In 1980, about 20% of China’s population lived in cities; today that proportion is about 65%. And there are so many cities now; 160 have populations of over one million people. That enormous transformation required new roads, bridges, railways, airports, power stations, schools, hospitals, and real estate development, both residential and commercial. Unfortunately, the debt incurred to make these investments will be difficult to pay off. Like the United States, China has a large government deficit; the International Monetary Fund puts it at the equivalent of 7.1% of GDP in 2023 and expects it to rise further (see the chart below). At the same time, the population is aging at an alarming rate, as discussed in the previous edition of Independent Thinking. The government will need to increase spending on social services to accommodate the needs of the growing older population. As approximately 70% of household wealth is tied up in the property sector, future wealth creation in the country may be imperiled, and citizens are increasingly likely to be reliant on government entitlements in their retirement.

While we worry in the West about inflation and persistent high interest rates, in China, with inflation flatlining over the last year, deflation and future growth are the pressing concerns, as evidenced by the paltry 2.7% yields on 10-year central government bonds. It is likely that strong sovereign support will contain any issues stemming from LGFVs, at least for the time being. But the combination of high debt, rising deficits, and aging demographics should impinge on China’s long-term growth rate.

At the same time, rising tensions with the United States are suppressing trade and limiting access to some technologies. While forward price to earnings ratios in Chinese stocks are below the long-term historical average and below that of many other global equity markets, they are reflective of a dimming earnings and economic growth outlook. This makes direct investment in China’s stock market less appealing than it’s been at any time since it was admitted to the World Trade Organization in 2001. We are also mindful that China’s economic challenges may reduce the trajectory of global growth and limit the growth of companies and countries with significant reliance on China.

At present, we are limiting exposure to China in our allocations, relative to their benchmarks. We remain open to targeted investments in the country, as the country’s stock market is too big to fully ignore, and there are likely to be pockets of innovation and productivity gains as urbanization continues and the country becomes less reliant on western technology. At present, however, China’s heavy debt burden is an obstacle to growth.

Brian Pollak is a Partner and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].