Independent Thinking®

Delayed Impact: the U.S. Deficit and Investors

August 1, 2019

The United States is running a $1 trillion – and widening – deficit. That’s despite a robust economy and a 10-year bull market, now the longest on record. But even as new debt piles up on top of old, investors and politicians remain sanguine. How long can this last?

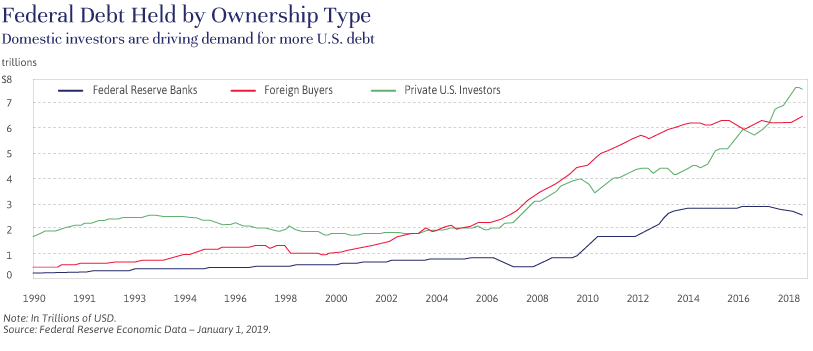

Demand for U.S. Treasuries may be the best indicator. While demand is more difficult than supply to measure or analyze, it appears that the desire to own our bonds remains sky-high, notably among domestic investors. The world buys Treasuries, in part because the U.S. dollar functions as the global reserve, and in part because returns, while near historic lows, are nevertheless better at present than those in many other industrialized countries. Although global appetite remains constant, U.S. investors are driving the recent surge in demand, as illustrated on the chart shown below.

Why is domestic demand so high? It’s because the private sector of the U.S. economy – households and businesses – are financially healthy and growing. Corporations are generating record profit margins, jobs are plentiful, wages are growing, and aggregate balance sheets are strong. This private sector demand managed to digest the $600 billion offloaded by the Federal Reserve over the past 18 months as part of its effort to shrink its balance sheet in the long wake of the 2008 financial crisis – and there is no sign of that appetite abating anytime soon.

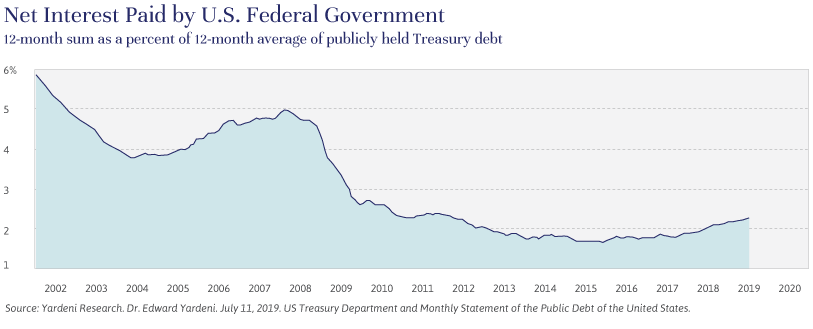

A healthy economy can serve as a reason to reduce debt. Now, it is serving as a reason for the government – and prospective candidates – to take on more. Powerful, secular deflationary forces of changing demographics and technological innovation, as discussed in previous editions of Independent Thinking, are overwhelming any inflationary impulses, and the rate of interest on the national debt is not rising dramatically, even as the debt itself rises, as illustrated below.

Of course, low interest rates can only occur when inflation and, most important, inflation expectations are also low. Inflation is generally considered the ultimate constraint on any government borrowing in its own currency. Investors will demand higher interest rates if and when they believe that the excessive borrowing and spending will force the government to effectively devalue the currency and raise inflation. Clearly, we aren’t hearing the political cries for austerity that we might otherwise expect in these circumstances, as we aren’t experiencing anything like the normal consequences of high deficits and debt.

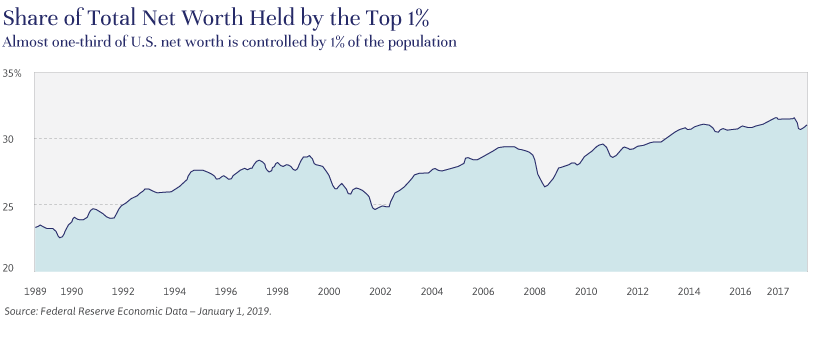

Instead, we are experiencing a seismic shift in wealth distribution. The strong domestic private sector demand for investment is narrowly sourced, with just 1% of households controlling 31% of net worth, compared with 23% in 1990, as illustrated below. This changing distribution has been a boon to the markets, as the concentration of wealth among the investing class has helped boost asset prices. Some of the incremental savings and investment flows to riskier asset classes such as stocks, private equity and real estate but a significant proportion is allocated to relatively safe investments, no matter how low the returns.

Consider Europe, where trillions of euros are invested at negative interest rates, presumably because the downside is effectively capped, at least in nominal terms. (And the real return could end up being positive in the event of deflation.) It’s a similar story in Japan, as discussed in Brian Pollak’s article, Modern Monetary Theory and a Free Lunch.

At present, the government is getting the nearest thing to a free lunch, running a $1 trillion deficit while the interest rate it pays on its debts declines. But it looks like politics will eventually drive the government to ever- increasing deficits until the negative consequences become a reality. In the interim, the continued strong demand for U.S. Treasury debt at very low interest rates suggests that investors are not yet piling into risky assets with anything like the abandon that signals a market top. We remain fully invested in growth assets and continue as appropriate to rebalance portfolios as those assets appreciate to meet each client’s unique goals.

John Apruzzese is the Chief Investment Officer of Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].