Independent Thinking®

Demographics and Development

May 7, 2019

Thomas Robert Malthus predicted in his 1798 An Essay on the Principle of Population that human population, about one billion at the time, would soon begin to double every 25 years, eventually causing global food shortages.

The population has since grown sevenfold, so he was right about massive growth, albeit at nothing like the rate he expected. However, he was wrong to doubt our ability to rise to the challenge, through advancements in agriculture, health, energy, trade and transport.

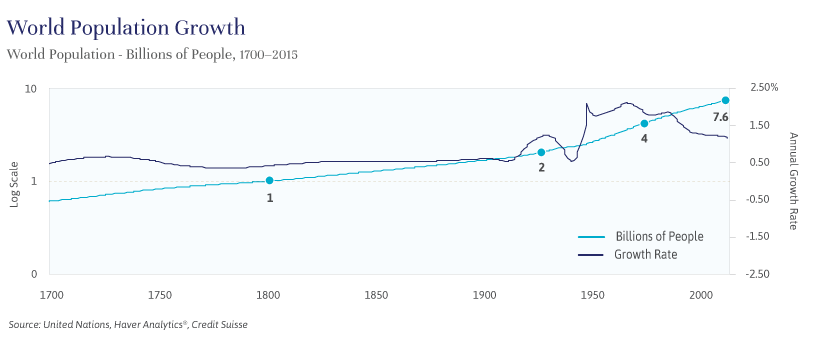

Global population growth is simply a function of the rates of births and deaths. Both were relatively high until the 18th century, nearly canceling each other out. Families needed to be big, to sustain the ravages of famine, disease and war. In the early 1800s, more than seven children, on average, were born in the United States to each woman. During Malthus’s lifetime – he died in 1834 – population growth started to accelerate as death rates plunged. As illustrated by the chart below, the pace of growth continued to increase for another century-and-a-half.

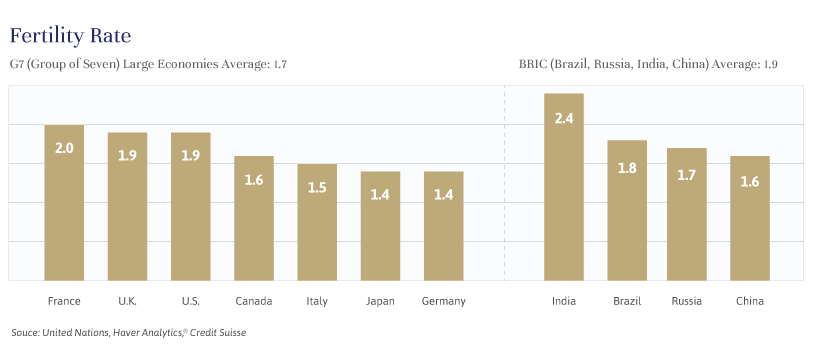

In the first half of the 20th century however, birth rates in many countries started to taper off. As industrialized economies replaced agrarian ones, big families went from being a boon (more bodies to farm and work) to being a burden (more mouths to feed and minds to educate). Today, fertility rates in all industrialized countries are below the replacement level of 2.1 births per woman. (The average in the G7 [Group of Seven large economies] is currently 1.7 – see chart below). The rise of service-based economies since the end of the last century has reinforced the trend to smaller families. More educated societies, most notably those with educated women, are waiting longer to have children and having fewer of them.

Many people still do worry about the impact of existing and continuing human overpopulation, especially regarding the very real risk that climate change will soon forever change the way we live. Globally, the population continues to rise and the United Nations projects 9 billion people by the end of this century, up from around 7.6 billion today. Emerging markets, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, southeast Asia, and India are certainly still struggling with rapidly growing populations, as birth rates remain high and death rates decline.

However, this is a situation not at all dissimilar to that experienced a couple of generations ago in now developed countries. And as information and technology spread faster, there is reason to believe that the emerging economies and their demographics will more quickly evolve. Indeed, many emerging economies are already near or below replacement fertility levels (Thailand [1.5], China [1.6], Russia [1.7], Brazil [1.8], Malaysia [2.1], Mexico [2.3]). Populations in these countries may soon begin to decline. In the Philippines, to take another example, the fertility rate of 3 children per woman is down from 7 in 1965. Over that same time period, India has gone from a rate of 6 to 2.4. At current projections, both the Philippines and India’s populations will be below replacement levels in just ten years.

That’s why some academics speculate that these global population growth rates will drop faster than the United Nations expects. In Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population Decline, authors Darrell Bricker and John Ibbitson argue that the global population will soon begin to decline, dramatically reshaping the social, political, and economic landscape. The benefits are considerable, notably to the environment and to the living conditions of women in the developing world. But as John Apruzzese writes in his article, Prospering in a Low-Growth World, aging populations and worker shortages may restrict economic growth, with long-term repercussions for investors. How economies manage this disinflationary transition will be a crucial part of their economic success or failure.

If Malthus were alive today, he might appreciate the power and potential of human ingenuity in confronting the demographic challenge he identified. But the shift toward a shrinking population may be the more relevant conversation now.

Brian Pollak is a Partner and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].