Independent Thinking®

Florida Bound: Moving to a Warmer [Tax] Climate

August 1, 2019

When the Beatles released Taxman in 1966, the band members were subject to tax surcharges as high as 98 percent. Within a few years, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks (who wrote Sunny Afternoon, another song about the surprisingly rock ‘n roll subject of tax), David Bowie, Cat Stevens, and many others had fled Britain. Americans have never had that option. Unlike those of all other developed countries, citizens and permanent residents of the United States are taxed on worldwide income.

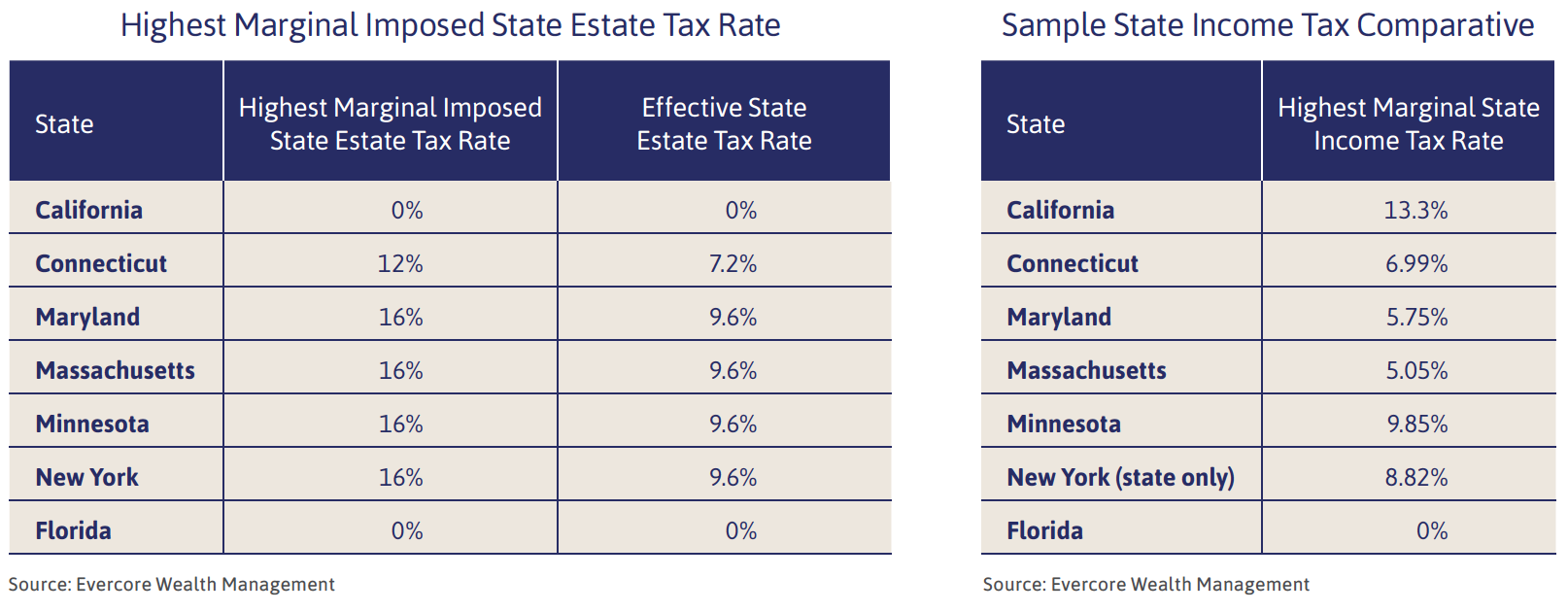

Tax exile in the United States tends to be a domestic affair, as families move from high-tax to low-tax or no-tax states. The differences can be startling – 8.82% personal income tax and up to 16% in estate tax in New York; none in Florida – as illustrated in the sample charts below. Just how important a role personal tax plays in these moves is difficult to measure, as Howard Cure notes in his paper titled, Federal Tax Reform and the Municipal Bond Market. The real drivers can, of course, include corporate tax advantages, the climate, and recreational interests.

In any case, the tax angle can be a headache. State taxing authorities are increasingly aggressive in challenging moves. Each state has its own rules on whether a taxpayer is subject to their income tax, but most include a count of how many days the self-declared former resident spends in his or her former domicile, with six months the general line in the sand. In New York, which is losing tens of thousands of people to Florida each year, more than to any other state, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, a person is still considered a resident for income tax purposes if he or she spends 183 days or more in the state.

While the terms residence and domicile are often used interchangeably, they have very specific meanings for both income tax and estate tax purposes, as defined by individual state laws. Residence simply requires physical presence in a state, while domicile requires physical presence in the state and the intent to make that state the fixed or permanent residence. While a person can have a residence in many places, as a general rule, they can only have one domicile.

The more substantial the retained property, the more intense the scrutiny is likely to be. Where are the people and objects that are considered near and dear to the taxpayer? Business and family relationships, children’s school attendance, credit card receipts, travel documents, E-Z pass transactions, phone records, vet bills and more; name it and state authorities have probably thought to examine it to verify the taxpayer’s assertions.

The burden of proof falls on the taxpayer, not on the state. The individual must be able to show that not only has he or she spent the required time out of the state at another residence but also that the intention is clearly to change the domicile. While there is no bright line test that determines domicile, individuals can draw on all of the same materials in their defense, in the event of a residency audit. Location apps, which use cellular network, Wi-Fi, and GPS technology to determine location, can augment hard evidence.

It should be noted that there is no double jeopardy when it comes taxation. More than one state could claim that a taxpayer is resident for income tax purposes and likewise could claim that a decedent was domiciled in the state for estate tax purposes. While these instances are rare, residency audits are not – and they are nothing to sing about. Taxpayers who wish to change domicile – for whatever reason or combination of reasons – should follow a clear protocol (click here to download checklist), be mindful of the potential traps, keep meticulous records, and seek expert advice.