Independent Thinking®

Inflation, But Not As We Usually Know It

February 26, 2021

Inflation, said the late economist Milton Friedman, is taxation without legislation. In that context, it’s not surprising that the strikingly low consumer price inflation of the past 20 years continues to support outperformance in both stocks and bonds. But other forms of inflation are on the rise, threatening future returns.

Let’s take a look at the three main types of inflation: consumer price, monetary and asset price. The interaction among them will be a significant driver in the markets and bears close watching.

CONSUMER PRICE INFLATION

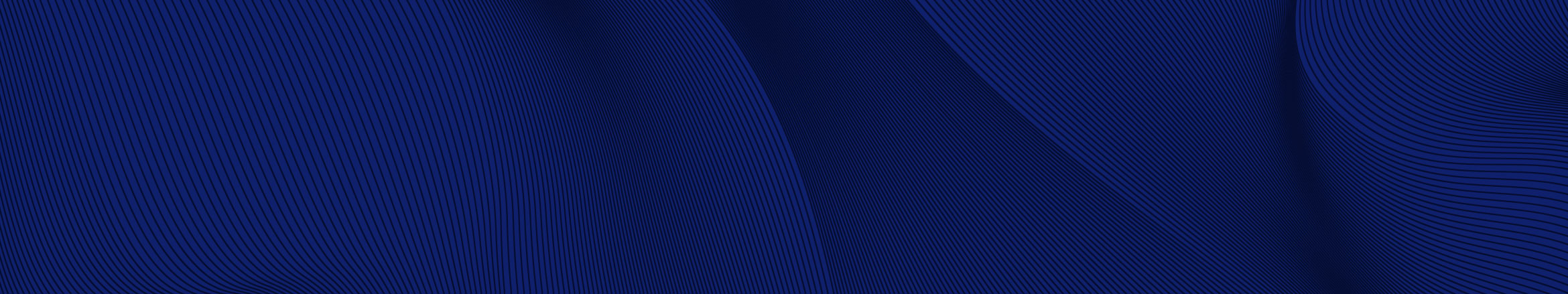

Price inflation is the price of goods and services experienced by both consumers and producers. The primary metrics used to measure consumer inflation are the Consumer Price Index, or CPI, and the Personal Consumption Expenditure Index (PCE). Both measure a market basket of consumer goods and services, but use different formulas and basket constructions. Both are important, but the PCE is the measure on which the Federal Reserve focuses most of its attention. While the Fed has a stated inflation target of 2%, both indexes have largely fallen short of the market over the past 10 years and appear to remain in decline.

The secular forces holding back consumer price inflation have included high debt levels, technological change, aging demographics and increasing globalization, and collectively they remain a considerable force. But the rising tide of monetary inflation might change that equation.

MONETARY INFLATION

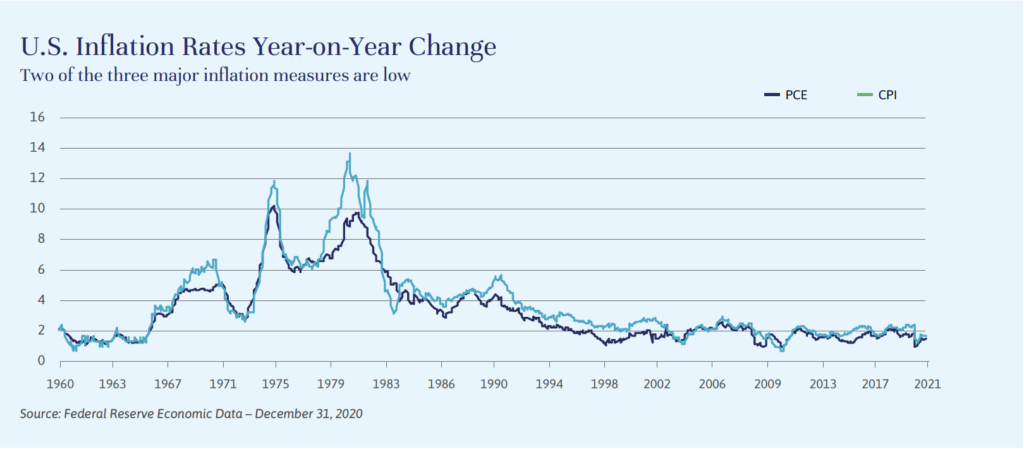

Monetary inflation generally refers to increases in the supply of money, and is most commonly measured by the monetary base or “MB”, which includes currency in circulation and money held in the reserve accounts of Federal Reserve member banks. MB represents the liability side of the central bank’s balance sheet, while government debt (e.g., U.S. Treasuries) or other securities purchased by the central bank represent the asset side. As with any balance sheet, assets must match liabilities, so increases in central bank bond purchases simultaneously increase the monetary base. MB is tightly tied to “M2”, a broader definition and a calculation that includes cash, checking and savings deposits, money market securities and funds, as well as other easily convertible “near money” deposits. M2 is closely watched as an indicator of money supply and inflation. A rise in MB drives M2 higher, as illustrated in the chart below. The significant increases in both Treasury purchases by the Fed and Treasury issuance in 2020 by the government have led to a corresponding spike in M2 not seen in over half a century.

Recent events have undermined the conventional wisdom that there is a direct correlation between M2 growth and consumer price inflation. The Federal Reserve, along with all developed central banks, has increased the size of its balance sheets to historic levels.

This began post the financial crisis of 2008-2009, slowed briefly late in the last decade, and accelerated to historic records since the COVID-19 crisis began. Yet the inflation experienced by consumers has remained under the Fed’s target rate through this period of epic balance sheet expansion. Consumer inflation is even lower in Japan and the European Union, despite even more aggressive monetary policy actions.

ASSET PRICE INFLATION

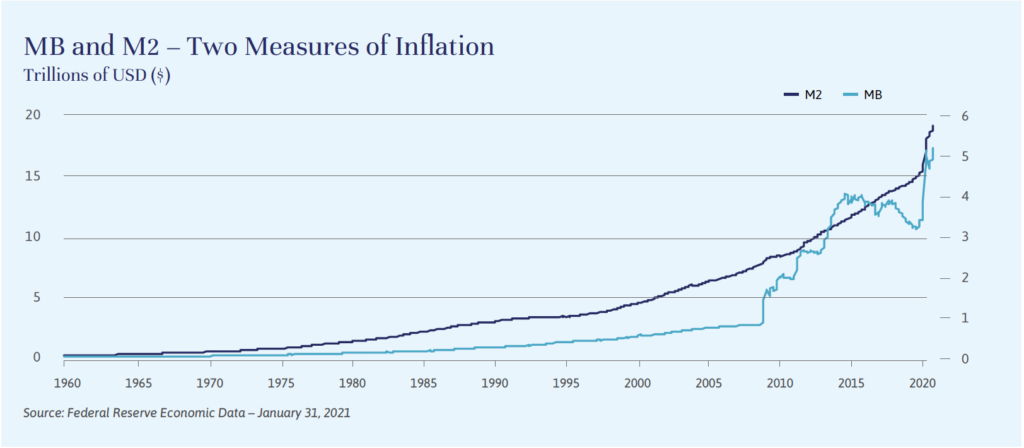

It is clear that the money supply has leaked into the economy, but primarily in the form of asset price inflation. Monetary inflation impacts asset price inflation by creating excess liquidity and a lower discount rate, both of which allow for higher valuations. Fed treasury purchases push bond yields lower, encouraging savers to take on more equity and (lower quality) bond risk, to earn more return.

The central bank balance sheet (MB) expansion and M2 stock increase have inflated financial assets, most obviously stocks and bonds, but also real estate, gold, Bitcoin, and collectibles like fine art. Again, the conventional wisdom has been challenged, as we still have not seen evidence of consumer price inflation in the economy – but asset inflation, along with M2 growth, has moved higher faster and more fiercely than in 2009.

Household net worth, probably the best metric to understand broad-based asset inflation, hit a U.S. record in absolute terms in the third quarter of 2020 at $123.5 trillion, according to Federal Reserve data. Much of the value of U.S. household net worth derives from ownership of equities, bonds and real estate. On a relative basis to disposable income and to GDP, it is near the post-WWII high and at the post-WWII high, respectively.

It’s worth noting that asset inflation has primarily accrued to the wealthier part of society. Only slightly over half of U.S. households have a stake in the stock market, according to a Gallup poll conducted in 2020, but a separate Federal Reserve report shows that the wealthiest 10% own over 87% of the equities. Real estate is slightly more egalitarian, with 67% home ownership rates, but again, by dollar value, much of this is concentrated at the top. As wage inflation is a prerequisite for sustained consumer inflation, wage inflation that is equal to or especially in excess of consumer inflation would be one way to help alleviate this wealth disparity. It would mean less fiscal spending would be required for transfer payments, reducing the need for fiscal deficits and for aggressive monetary policies.

As discussed in the cover article of this issue, the potential for monetary and fiscal policy expansion to push consumer prices higher is far from a given. But it may be the single biggest risk to a traditional portfolio of stocks and bonds, as significantly higher consumer price inflation would likely take significant steam out of asset prices. While our base case remains a continued period of low inflation, we will continue to diligently monitor the factors that drive longer-term inflation and consider investments that could offer protection. As always, diversification of risk and appropriate asset allocation is our best defense against any long-term risk, inflation included.

Brian Pollak is a Partner and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].