Independent Thinking®

Investing in a Low-Resource World

June 30, 2022

It took just three months for COVID-19 to spread around the world, followed by supply chain shocks and now persistent inflation, a reminder of just how interconnected we all still are.

But globalization, in spirit and in practice, is in retreat and cracks are appearing throughout the U.S.-centric trade and finance system. In an increasingly resource constrained world, risks and opportunities for investors may need to be recalibrated.

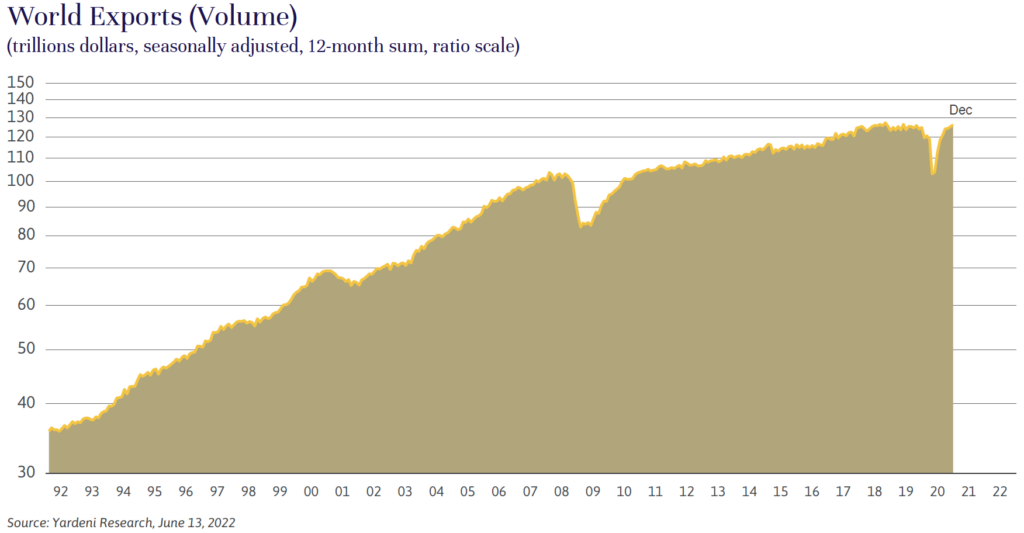

Take a look at the chart below. Global trade took off in 1991, with the end of the Cold War. And it really got going after 2001, with China’s participation in the World Trade Organization, sparking years of growth that lifted millions of people throughout the developing world out of poverty. Global access to the natural resources previously locked behind the Iron Curtain – and to the huge labor and growing consumer markets in China – paid significant dividends, notably to multinational corporations. U.S. investors and Americans generally benefited from the world’s willingness to retain trade gains in U.S. dollar-based assets, allowing the United States to finance its ongoing trade deficit.

The United States and China effectively pressed rewind on globalization about five years ago, when the United States implemented stiff trade tariffs on Chinese goods and China became more autocratic and less capital-friendly.

And Russia has critically compounded fears of a new Cold War with the invasion of Ukraine. As of March 2022, global trade volumes are down 0.9% from the end of 2021, and growth projections continue to decline for 2022 estimates.

Now, U.S. companies are scrambling to onshore manufacturing or to at least diversify their sources away from China but are finding the effort neither easy nor inexpensive. Many tech companies, such as Google and Amazon, have pulled some of their businesses out of China, but at present, the United States remains dependent on both Chinese consumer goods and on semiconductors produced in Taiwan and South Korea.

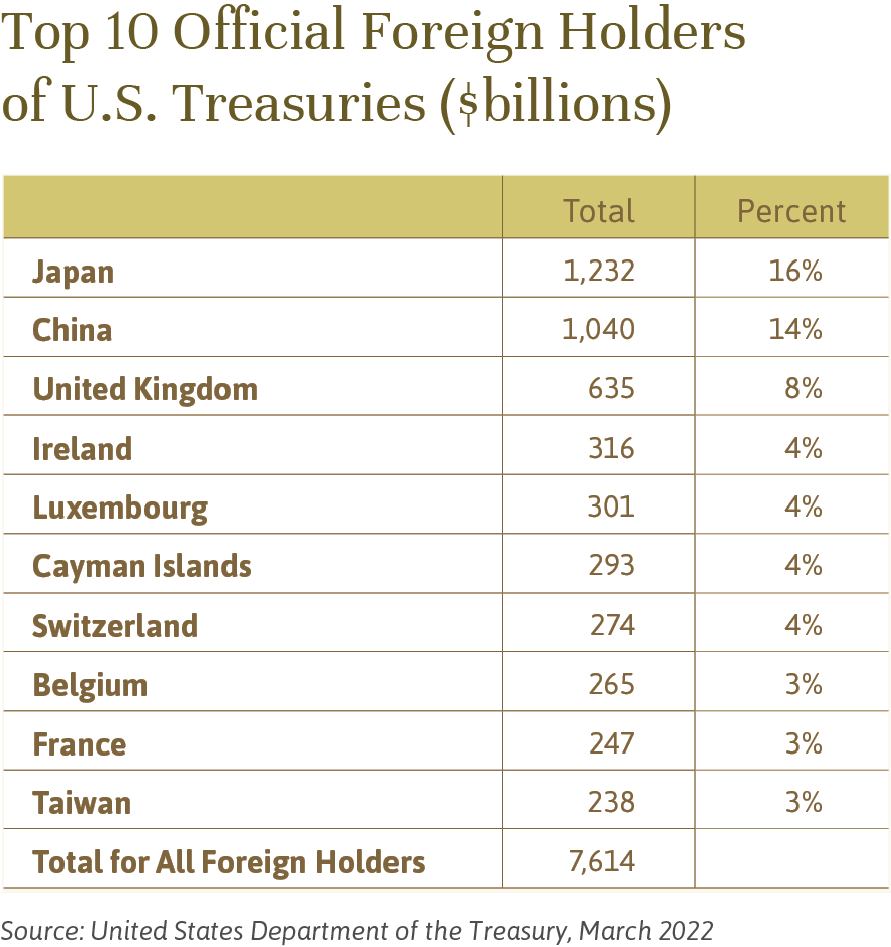

China has stopped buying U.S. Treasuries. That’s been okay so far. As illustrated below, alternatives for global investors are limited and total demand for U.S. dollars is still high.

U.S. energy independence is good news, of course, but it does mean that the United States has less incentive to guarantee the security of international trade routes and stabilize the Middle East. Consider the trade disruption underway as Europe scrambles to reduce its dependence on Russian oil and gas, a difficult transition in the long term and almost impossible in the short term. The Persian Gulf countries produce 30% of the world’s oil, compared with Russia’s 10%, so the potential for trouble is that much greater.

Russia and Ukraine are also major exporters of wheat, vegetable oils and fertilizer, and the resulting shortages are exposing vulnerabilities around the world. Consumers everywhere are being hit with high prices for essential foods and, as always, the poorest are being hurt the most. Geopolitical alliances could shift in favor of China and Russia as governments in developing countries try to ward off starvation.

The high inflation rates that we and the rest of the world are now experiencing are a negative for almost all investment asset classes. Investors force values down as inflation mounts, not because the underlying assets are necessarily deteriorating, but to increase the future nominal expected return to make up for the higher inflation rates. Eventually, stocks should be an inflation hedge as well-managed companies adjust to the new reality, but that takes time.

It’s tempting to consider hedges. But attempting to invest in short-term inflation hedges can be a dangerous game. Commodity prices move up rapidly during an inflation shock, as they have recently, but the long-term returns from investing directly in commodities is very poor. Commodity producers present an opportunity, but timing is critical; most commodity producers are not good long-term investments because they tend to lack a competitive advantage. And Treasury inflation protection bonds, or TIPs, are not as helpful in combating inflation as one might think. They have generated a negative return this year through May 31 because real interest rates have moved up along with inflation, causing TIPs prices to fall. Only when real interest rates reach an acceptable level do they become a good inflation hedge. The real yield on the 10-year TIPs has only just turned positive, so we will be watching this market closely.

For investors, there’s a lot to think about. This is a good time to revisit both long-term goals and attitudes to risk, as Jeff Maurer discusses here, and to review capital market assumptions. Our balanced composite has experienced about an 11% drawdown so far this year.1 If we have a recession in the next 12 months, on which we are at present assigning a 40% probability, balanced accounts could drop another 10% or so as the stock market prices in falling earnings, in addition to the valuation reduction that we have already experienced. (See the article here addressing our focus on investing in high-quality companies.) The yields on longer-term bonds out 3-10 years are starting to get interesting but could go higher if inflation is not contained, so caution is warranted in this asset class as well.

Our primary focus at present is on wealth preservation, and we remain confident long-term investors. We continue to rebalance portfolios and reexamine risk tolerance, in the context of individual client goals and tax considerations. We are maintaining sizable allocations to defensive assets, as well as to illiquid investments, again as appropriate for each client. Finally, we continue to overweight the United States, as we have done for years, a position that has served many of our clients well. In this resource challenged environment, the United States is not immune, but we are relatively self-sufficient, in food and many other commodities, as well as in energy.

John Apruzzese is the Chief Investment Officer at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].

1 The performance results of the balanced composite are based upon the returns of fully discretionary managed accounts with a designated investment objective of Balanced and no investment restrictions. The performance results mentioned are net of fees reflecting the deduction of actual fees of the accounts included in the composite and are through 5/31/22.

Betting on the Greenback

China’s pullback in new purchases of U.S. Treasuries is only the latest challenge to the U.S. dollar’s 60-year supremacy; others have included the formation of the European Monetary Union, the rise of Japan and China as global economic powers, and other changes to the international monetary system.

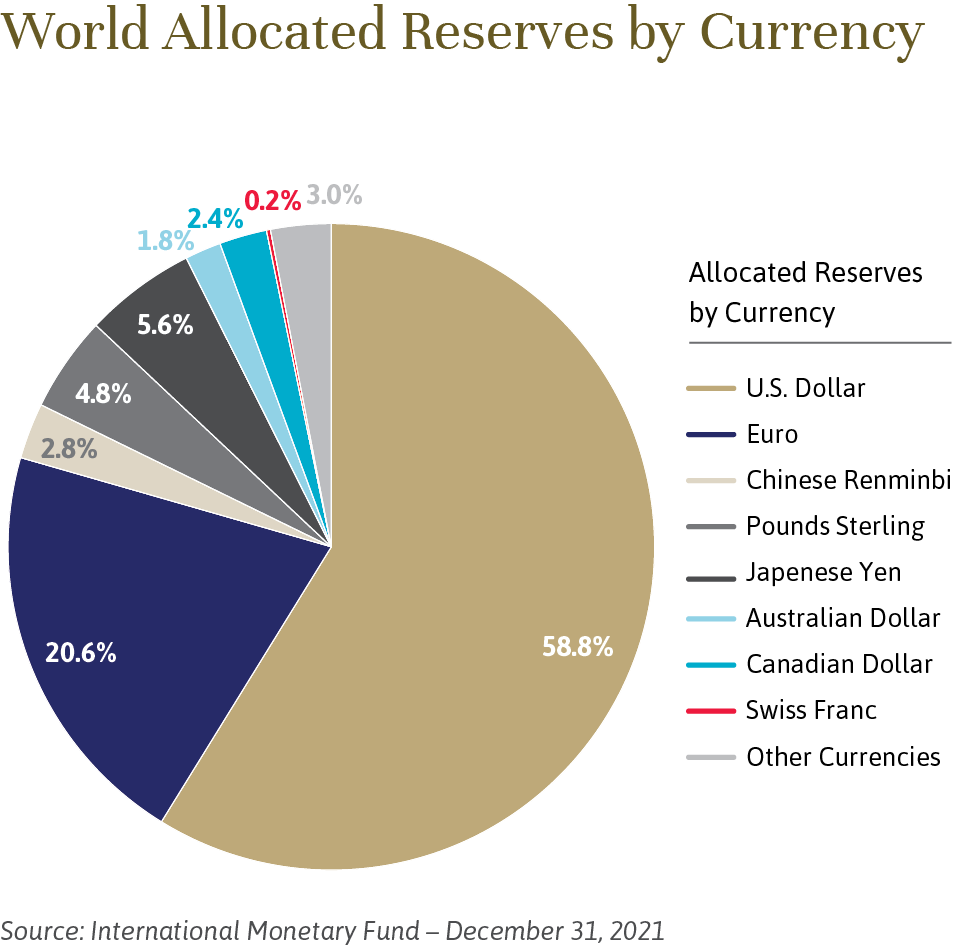

But the size of the U.S. economy, its importance in international trade, and the depth and openness of its financial markets have so far preserved the dollar’s status. It continues to serve as the world’s primary reserve currency, meaning countries around the world, as illustrated below, choose to hold large amounts of U.S. dollars for transactions, trade and monetary value preservation.

As John Apruzzese discusses above, this long-term global preference for U.S. dollars has benefited the United States in major ways, lowering the cost of capital for its government and corporations, and strengthening the purchasing power of its citizens. From Wall Street to Main Street, this is a big advantage and one of the reasons we remain overweight to the United States in our portfolios.