Independent Thinking®

New York State 2020: The Municipal Bond Outlook

January 22, 2020

Investors in New York debt are eager to hear how the state’s legislators will grapple with a projected $6.1 billion fiscal deficit, the largest in a decade. Howard Cure, Director of Municipal Research at Evercore Wealth Management, reviews the outlook for the state. Read more below.

INTRODUCTION

The origins of the Empire State’s nickname are unclear but may be rooted in New York’s relative riches and resources.

These have long supported generous funding for healthcare, education and other government programs, as well as one of the best funded state pension systems in the country. Almost a quarter of the state’s operating fund is now consumed by its Medicaid program, and that proportion continues to grow, up from 20.4% in the prior two years, impacting the New York budget as a whole.1 Further exacerbating this budget imbalance is the perennial dispute of how much and to whom is distributed in-state aid for education. Investors in New York debt are eager to hear how the state’s legislators will grapple with a projected $6.1 billion fiscal deficit, the largest in a decade.2

Usually, projected state budget gaps of this magnitude result from some combination of previously instituted and recurring spending programs and revenue declines. Revenues, while slowing, are still growing. State receipts have grown 3.5% annually on average and are projected to grow 2.1% a year on average between fiscal years 2020 and 2023. 3 There are concerns about raising additional tax receipts by increasing the income tax rates on the state’s wealthiest citizens under the changes wrought by the Federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which limited state and local tax deductions. Given the progressive nature of the state’s income tax system and the outsized impact the top tier pays in total state income tax receipts4, an additional tax surcharge could lead to an exodus of these individuals and further erode the state’s tax base.

Still, New York has one of the broadest-based, mature and wealthy state economies in the country and continues to attract a highly educated and global workforce. The state has the financial capability to balance its budget without eviscerating its safety net or education programs. This will require legislative cooperation to more efficiently and equitably allocate resources without overburdening taxpayers in an already very progressive tax system.

MEDICAID

Medicaid state spending increased 0.8% annually on average between 2011 and 2017, but has increased 6.1% annually on average between 2017 and 2020.5 (New York’s relative control over Medicaid spending from 2011 to 2017 is largely attributed to Governor Cuomo’s initiative on Medicaid Redesign as described below). New York’s Medicaid costs are not only growing, but they are comparatively high, with per Medicaid spending per capita the highest in the nation and over 70% higher than the national average.6 New York’s high rate of spending is in large part the result of its expansive eligibility rules, broad enrollment, and relatively generous benefits.

Medicaid overspending has multiple causes. Recent hikes in the state minimum wage have increased Medicaid costs because healthcare providers are eligible for higher reimbursements as their labor costs rise. In addition, Medicaid long-term care enrollment (nursing homes) increased 12% in 2019, more than twice the expected rate of growth.7 While long-term care costs are escalating nationwide as the population ages, New York’s per capita spending is well above average. The State Budget Director also cites the phase-out of enhanced federal funding to support Medicaid expansion, increased Medicaid enrollment, and payments to distressed hospitals as contributors to rising costs.

Medicaid requires all states to provide health services to anyone who qualifies, but the state could reduce costs for supplemental programs and the reimbursement rates to providers that contract with the state.8 Under the Affordable Care Act the state has increased the number covered in the state Medicaid program by about 50% over the past decade to 6.3 million people.9 However, spending increases have exceeded the implementation of a state “global cap,” as described on page 5, that is linked to the rate of inflation. When enrollment leveled off after 2016, the cap allowed spending to keep going up and per-recipient costs quickly climbed. Since the federal government provides matching funds for Medicaid, New York has to take into consideration that any state cuts to the program will have an outsized impact for funding.

Overhauling the costly public insurance system may also be difficult as the hospital employee unions, doctors’ groups and the hospital associations exert a tremendous influence over legislative matters pertaining to healthcare. And while Medicaid budget imbalances have only recently received public attention, the problem has been brewing for some time. Last year, the state deferred $1.7 billion, or 8% of its Medicaid spending by three days, pushing the costs into the following fiscal year’s budget.10

EDUCATION FUNDING

Rising education costs are also affecting the New York state’s budget. New York education aid increased 3.7% annually on average over the past decade, twice the rate of inflation.11 And the distribution of this aid is also a growing issue. As noted by the Citizens Budget Committee, wealthy districts with sufficient local resources to provide a sound basic education nevertheless received $1.6 billion in state school aid out of total state Foundation Aid of $18.4 billion.12

The controversy over public school funding in New York State can be traced back to a 2006 court decision in the Campaign for Fiscal Equity v. State of New York. In this case, the court essentially ruled that New York City schools had failed to provide a sound basic education to all its students – a situation that the state had to rectify by transforming its approach to funding public schools. The formula determines the total district resources needed by specifying a base per pupil amount and then adjusts it for special student needs in each district, along with regional cost differences and local district’s funding capacity. While a new formula was established, its implementation was disrupted by the Great Recession and a period of political instability that saw three governors in less than three years (Elliot Spitzer, David Paterson and Andrew Cuomo).

While Governor Cuomo has demonstrated in past years a willingness to increase public school funding, he balances that with his determination to adhere to a self-imposed 2% cap on overall state spending increases. The state budget and the school funding formula also reflect the political power of the two primary political parties. With the Democrats in control of both the Assembly and Senate, there could continue to be more of a funding emphasis on urban districts. The upcoming budget negotiations will likely be difficult given the size of the projected operating deficit and the likely inability to raise total education appropriations. Therefore, wealthier suburban districts may need to prepare for cuts in state appropriations.

REVENUES

While the overall state economy is strong, increasing taxes to address the budget imbalance may not be in the best long-term interests of the state. New York’s state and local tax burden is the highest in the nation and 48% higher than the national average.13 New York’s high tax burden combined with the federal cap on the deduction for state and local taxes, or SALT, increases the risk that high-income earners will move to lower tax states. Other, potentially more palatable, revenue solutions could include:

- Selling licenses for currently restricted or prohibited activities such as sports betting, casinos in downstate New York and the legalization of recreational marijuana

- Renewing efforts to impose a pied-a-terre levy on high-end second homes

- Increasing taxes on carried-interest and stock transfers

Potential revenues on these changes are difficult to assess, however, given their nature and variability. Effectively addressing expenditures such as Medicaid and education aid requires recurring revenue at a relatively level pace.

Compounding these difficult choices is the current condition of the state’s Rainy Day Reserves. The State Comptroller recently issued a report14 critical of the inadequacy of the current reserve fund levels limiting their value in the event of a fiscal emergency. The Comptroller’s report noted the combined current totals of the Tax Stabilization Reserve Fund and the Rainy Day Reserve Fund, at just over $2 billion, equate to little more than a third of their statutorily authorized levels. While the median rainy day holdings among all states with such reserves are estimated at 7.5% of General Fund spending, New York’s reserve funds total only 2.8%. The Comptroller recommends development of a multi-year plan that would raise reserve levels to mitigate the state’s next severe fiscal challenge. These reserves should be assessed at least annually with the need to establish policies by the legislature and Governor for how and when these resources can be drawn upon.

NEW YORK STATE DEBT

Spreads, the difference in yield between state debt and gilt-edged AAA rated debt, have tightened for the state of New York for a number of reasons. The market has recognized the state’s economic strengths and fiscal achievements over the last few years in controlling expenditures and raising taxes. And again, New York’s net pension liability meets its actuarially required funding and is among the lowest of any state, the result of years of scaling back pension benefits to new employees. There are now six tiers of pension benefits, with different vesting benefit and contribution levels. However, the state’s unfunded Other Pension Employee Benefits, or PEB, liabilities are high and growing due to underfunding of the actuarially determined contributions. The state set up a trust fund for OPEBs in fiscal 2018; to date, the trust has not been funded.

Market forces are also tightening spreads. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, or TCJA, eliminated the ability to advance refund debt issuances. As a consequence, total municipal tax-exempt volume is below recent yearly averages and increased demand is chasing less tax-exempt supply. The TCJA also implemented a cap of deducting state and local taxes. This has prompted investors in higher-tax states to seek tax-exempt income, which has led to significant inflows into municipal bond funds, especially funds targeting residents of high-tax states such as New York. In fact, inflows into tax-exempt bond funds have exceeded outflows for the past year.

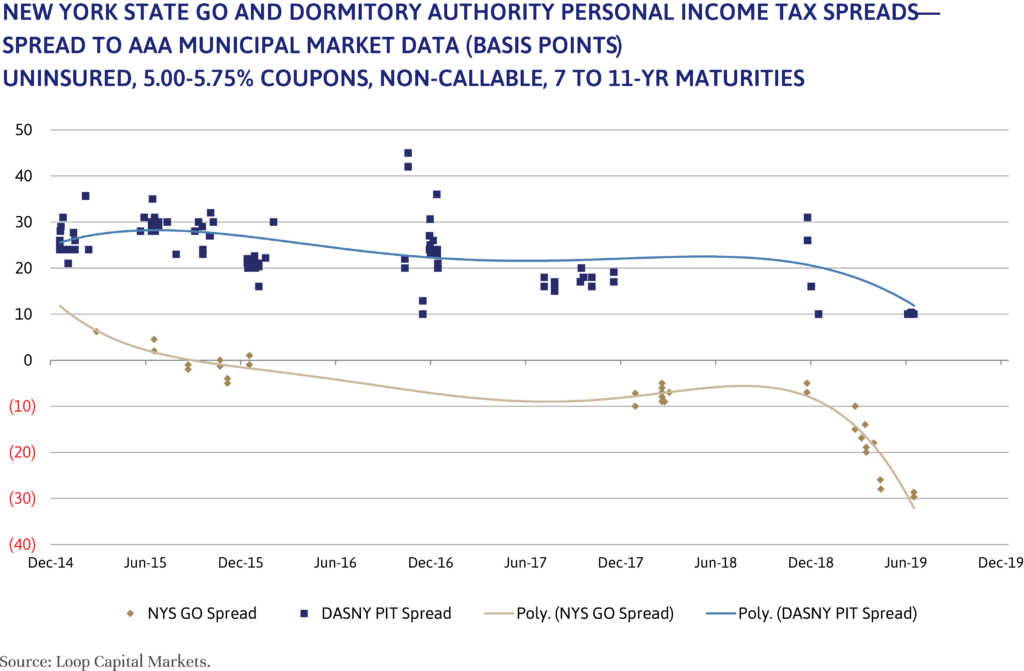

To demonstrate the market’s view of a credit situation, we typically select a state’s general obligation (GO) debt. As noted on the graph on the following page, to demonstrate tightening yields we have selected New York State debt secured by personal income taxes. We did not select New York State GO debt, which has approximately $2.3 billion outstanding, as it requires voter approval and represents less than 4% of total New York State obligations.

The state’s GO debt is in such short supply that demand is great and skews the measurement of yields compared to the AAA scale to such an extent that this debt trades at lower yields than the AAA scale as shown on the graph. State income and sales tax debt, which does not require voter approval, totals over $48 billion, representing 75% of outstanding state obligations, and is more representative of debt and demand. Spreads have tightened for both series beginning in 2014 for both pre- and post-TCJA showing causes to be a combination of improved credit circumstances and the impact from tax law changes to demand.

CONCLUSION

The Empire State continues to contain great riches and resources. At present, the state has a long way to go to structurally balance its budget and the dependencies associated with its progressive tax structure. It is, as always, vulnerable to fluctuations in the capital markets, especially since capital gains are a major source of income for New York filers with income of $1 million or more.15 New York has to grapple with state funding issues for Medicaid and school districts, as well as extensive capital plans that will continue to place a burden on the budget.

We continue to recommend avoiding New York State GO debt, not for concern over credit risk but rather for lack of yield. Instead, we recommend diversifying a New York portfolio with essential purpose revenue bonds and enterprise systems such as water and sewer issuers and public power systems, airports, and public and private university system debt, as well as various general obligation debt of the cities, counties and school districts that are more reliant on local property taxes than state aid to balance their operations. These should prove relatively robust if the state’s financial position deteriorates.

MEDICAID REDESIGN

When he took office in January 2011 – facing a $10 billion projected gap in his first budget – Governor Cuomo targeted Medicaid costs as a major cause of the state’s chronic financial ills. The governor and the legislature responded with a mix of immediate spending cuts – such as eliminating automatic “trend factors” that otherwise boosted provider fees every year – and longer-term management changes.

The changes included:

- Imposing a Global Cap on the state share of Medicaid, which limited annual growth to the 10-year rolling average of the medical inflation rate.

- Empowering the health commissioner to unilaterally cut provider fees if spending threatened to exceed the cap.

- Appointing a 25-member Medicaid Redesign Team of state officials and industry stakeholders to find the savings necessary to stay on budget.

The cap brought a measure of restraint to spending growth, especially in the context of rising enrollment. The commissioner’s additional budget powers, although never invoked, gave industry officials an incentive to collaborate on finding savings.

Current drivers of Medicaid costs include three basic factors:

- Enrollment: New York poverty rate is about average at 13%, yet the share of its population covered by Medicaid is 33%.16 New Yorkers with higher incomes can also qualify for Medicaid if they have uninsured medical expenses that would consume all or most of their earnings, or by using legal maneuvers to transfer or shield assets before entering a nursing home.

- Personal Care: In New York “Personal Care” provides non-medical services – such as cooking, house-cleaning and help with bathing – for disabled people living at home. New York recently spent $5.5 billion on personal care services, which was the most of any state by a factor of almost three.17

- Various Provider Subsidies: The Indigent Care Pool is designed to partially reimburse hospitals for providing free care to the uninsured and to supplement the relatively low fees paid by Medicaid. However, there is some controversy in the grants to wealthy hospitals versus true safety-net institutions. Two other subsidy programs, the Vital Access Provider Assurance Program and the Value-Based Payment Quality Improvement Program, effectively function as general assistance for financially struggling hospitals. The question remains for hospital recipients of these programs if they are needlessly subsidizing wealthy hospitals or propping up institutions that are no longer financially viable.

Howard Cure is the Director of Municipal Bond Research at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].

1 New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2020 Mid-Year Update

2 New York’s mid-year budget update reports a $6.1 billion budget gap next fiscal year (beginning April 1st, 2020), and a four-year gap of $22.2 billion out of an operating budget of over $102 billion.

3 New York State Division of the Budget, FY 2020 Mid-Year Update

4 Personal Income Tax Revenues in New York State and City, August 13, 2019: New York taxpayers with taxable income of $1 million or more accounted for just 1% of all filers and 37% of total state personal income taxes.

5 Citizens Budget Commission: “Overdue Bills Time to Face the Reality of Rising Medicaid Costs” October 9, 2019

6 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Expenditure Reports From MBES/CBES and Kaiser Family Foundation, “Total Monthly Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment” October 2019

7 Moody’s Investors Service: “State of New York Medicaid Spending Becoming Achilles’ Heel of State Budget” December 3, 2019

8 In fact, the Cuomo administration announced New Year’s Eve it would cut reimbursement rates by 1% – which is estimated to eliminate about $500 million due to be funneled to doctors and hospitals in the next budget, “Crain’s New York Business: Battle for Albany” December 2019

9 Empire Center: “Busting the Cap Why New York is Losing Control of its Medicaid Spending Again” October 2019

10 Citizens Budget Commission: “Overdue Bills Time to Face the Reality of Rising Medicaid Costs” October 9, 2019

11 Citizens Budget Commission: “Funding a Sound Basic Education in 2020” March 2019

12 Citizens Budget Commission: “Testimony on the Distribution of the Foundation Aid Formula as it Relates to Pupil and District Needs” December 3, 2019

13 Tax Policy Center, “Rankings of State and Local General Revenue as a Percentage of Personal Income” December 2019

14 Office of the New York State Comptroller: “The Case for Building New York State’s Rainy Day Reserves” December 2019

15 Net capital gains ranged from 21% to 44% of income for filers with income of $1 million or more over the last 10 years. Citizens Budget Commission, “Personal Income Tax Revenues in New York State and City” August 13, 2019

16 Census Bureau: “Percentage of People in Poverty by State Using 2- and 3-Year Averages” September 2019

17 IBM Watson Health: “Medicaid Expenditures for Long-Term Services and Support” May 2018