Independent Thinking®

Striking the Right Balance in Estate Planning

July 20, 2017

Most high net worth families want to reduce estate taxes. But in the drive to reduce their exposure, families can inadvertently bind themselves with excessively complicated planning structures or, worse, fail to retain adequate resources to meet their own needs.

Complicated estate plans often create multiple entities to leverage the use of the lifetime federal estate tax and generation-skipping tax exemption amounts (currently $5,490,000 for each individual). They can require pages of diagrams to keep an account of the structures and the flow of assets. For large estates of $15 million or more, these plans can make sense, if the supporting infrastructure is in place to implement and administer the plan, monitor its effectiveness, manage the ongoing tax compliance and keep up with evolving legislation. But the plan has to be constantly checked to keep the complexity (and added administration costs) proportionate with the real needs of the family.

As King Lear discovered, giving too much away during one’s lifetime is the other main risk in overplanning, especially as lifetimes lengthen. Most of us should expect to spend far more than our parents or grandparents did in later life, both for pleasure and for healthcare. (See the box below for some alarming statistics on the latter.)

Long-term Care: Old Age Isn’t Cheap

- About 70% of people currently turning 65 will require some long-term care in their lifetime.

- They will receive care for an average of three years.

- 22% of long-term care costs are paid out of pocket.

- Over 10% of the population age 65 and older has Alzheimer’s disease (about 5.3 million people in 2017), and 38% of those are over 85 years old, according to Alzheimer’s Association.

- The average yearly cost of nursing home care in the United States is $92,376; in some states it’s almost double that. And that’s before the costs for personal aides or nurses.

Even couples with large estates and high rates of spending may find it best to keep assets in their names and to make use of smaller lifetime gifts – up to the annual exclusion limit of $14,000 per person, or $28,000 per couple for each donee – and to make direct payment to medical or educational institutions on behalf of their beneficiaries as needed (as exclusions for these transfers are unlimited). In this way, they can help their family as needed while maintaining control over – and access to – their assets.

Market fluctuations can significantly impact lifestyles. While it might seem like there will be sufficient funds for the remaining years after transferring assets out of an estate, a big drop in the markets is unlikely to be accompanied by a similar decline in the cost of living. And it would be unwise to assume that inflation will remain low forever. Balancing estate planning and lifestyle goals is a key component of wealth planning.

An integrated financial plan should consider the whole balance sheet – all financial and nonfinancial assets and liabilities. It should include a lifestyle analysis of income and expenses that factors in a reasonable return and accounts for illiquid assets that may not be available for cash flow needs, and an estate plan analysis that includes all current obligations and diagrams estate flow and structures.

A baseline-planning model enables advisors to test potential planning techniques. If, for example, a couple would like to make a significant gift to their heirs during their lifetime, will they have enough assets to live on in the event of a big market downturn? This type of stress test, combined with a Monte Carlo simulation that runs multiple trials with randomized rates of return within certain parameters to evaluate the probability of a plan’s success, can go a long way in ensuring that the couple can meet their own lifestyle goals.

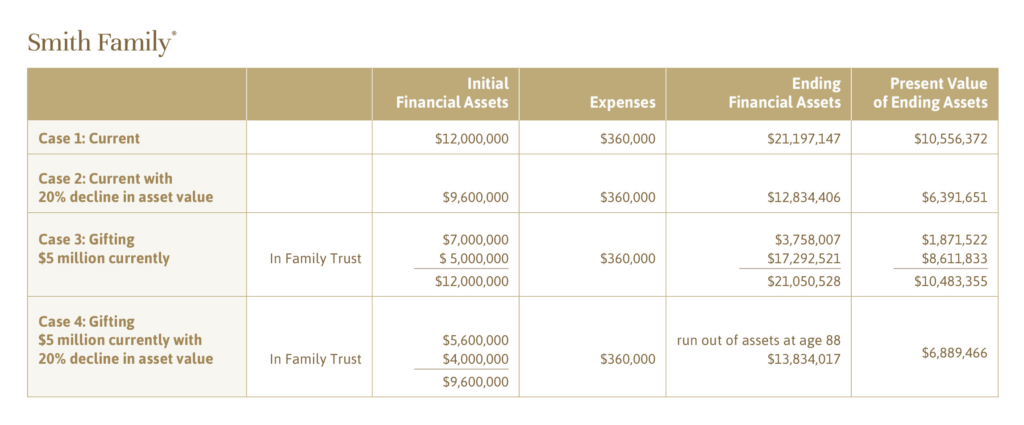

Consider the Smiths, a couple in their mid 60s with a total estate of $12 million in financial assets. They spend a reasonable 3% of their portfolio a year, or $360,000 after taxes, and can expect their expenses to grow at an annual rate of 3%, roughly in line with projected long-term inflation rate. Their assets should grow at an annual rate of 6.1% a year to over $21 million in 23 years.*

If we assume that the current federal estate tax exemption amount ($5,490,000 for each individual) grows over that same period at the assumed inflation rate of 3%, the Smiths will not have a federally taxable estate. For this couple, making a substantial gift in their lifetimes may not be appropriate, as they will not leave a taxable estate and doing so could impair their lifestyle in the interim.*

If the spending rate is greater than the 3% rate or if the rate of spending increases due to the added cost of healthcare, this couple could run out of assets more quickly. Once a baseline-planning model has been created, we can test possible planning techniques, such as the ramifications of making gifts now.

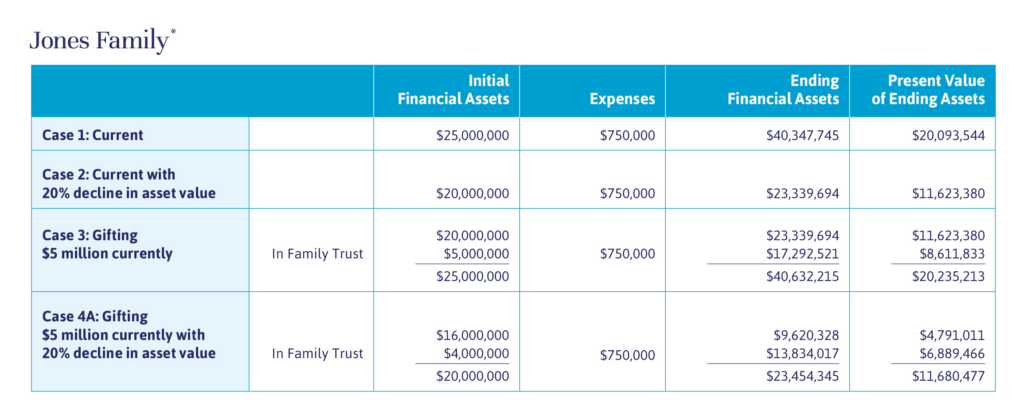

Let’s contrast that with the Joneses, a couple of the same ages with $25,000,000 and a 3% spend rate, who experience a 20% decline in asset value immediately after making a similar gift.

In this situation, proactive planning should be considered, as the Joneses will otherwise have a taxable estate, and would certainly benefit from tax-reduction strategies that accommodate their lifestyle needs and potential market fluctuations. For example, the use of a Spousal Limited Access Trust, or SLAT, can ensure that assets are available to the surviving spouse if really needed, such as in the event of an emergency (or in the type of drawdown illustrated in the fourth scenario in each chart), but the assets and the future appreciation will eventually pass to the heirs free of estate tax.

In planning, as so much in life, it’s critical to strike the right balance. Your Evercore Wealth Advisor can help you make the decision that is right for you and your family.

*Examples assume starting ages of 66 and 67, and the death of the oldest at 90. It also assumes a 6.1% rate of return and a 3% inflation rate.