Independent Thinking®

Sustainable Investing: What’s it to You?

June 24, 2021

Investors who care about sustainable investing often care very deeply, as a way to express their individual values and drive change. For something so personal, there can be no one right approach, no single lens. Portfolios should reflect the interests of the people they serve – and ideally at no cost to performance.

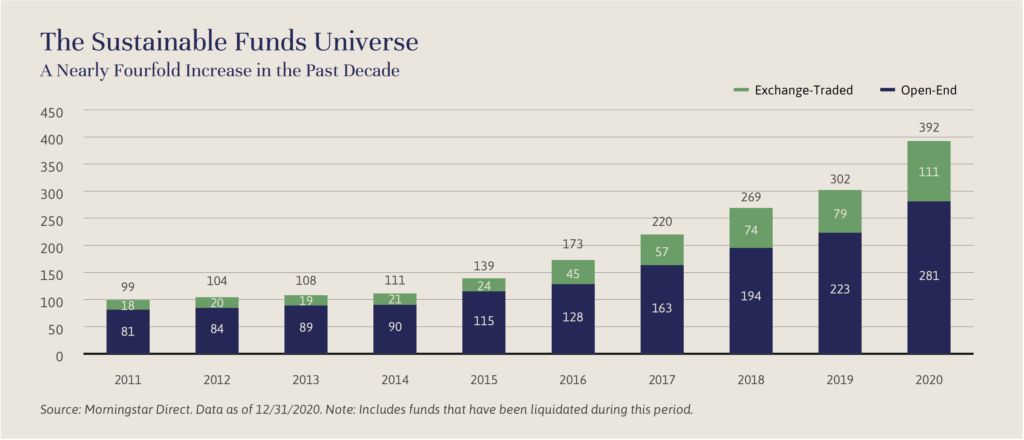

On the surface, it seems as if any and every interest can be expressed in this marketplace. There are now about 400 so-called sustainable mutual funds and exchange traded funds, or ETFs, in the United States alone, up fourfold in just over 10 years (see chart below).1

In 2020 alone, over $50 billion in net capital flowed into these investment vehicles. And these numbers appear likely to grow. The Federal Reserve and the Biden Administration have stated explicitly that climate change and a transition to a more sustainable economy are important economic policy tenets. Corporate boards and CEOs are not far behind, with increasingly frequent references to corporate ESG policies and disclosures. And many large investors, notably BlackRock, the world’s largest asset management firm, are pressuring investors and corporations alike to make a more significant commitment to advancing ESG concerns.

But choice can, as any consumer knows, breed confusion. Portfolios and the indices they benchmark against are often tilted toward certain environmental, social and governance, or ESG, factors, such as avoiding exposure to high levels of carbon emissions or the use of child labor, and tilting exposure toward board or C-suite diversity or good corporate governance. While the approaches afford investors more opportunity for customization, the individual E, S and G elements can be perceived differently and don’t necessarily work well together in evaluating exposures. (See the box at the end of this article for a guide to these terms.) Focusing on broad ESG indices as benchmarks can also cause investors to lose sight of the whole and lead to surprising outcomes, such as the inclusion of oil producers or handgun manufacturers in so-called sustainable funds or other unanticipated exposures.

Consider Facebook, Inc., which for several reasons is not a priority holding in our core equity strategy, but is often referenced by other investors as an ESG-friendly holding. According to data from Refinitiv Financial Solutions, Facebook’s overall ESG score is a B- as of this writing, with an A grade in resource usage mitigating lower grades in governance and social pillars. But when data around privacy and competition controversies are factored in, Facebook’s combined score falls all the way to C-. These controversies are not factored into the traditional ESG scoring methodology, but their presence creates valid potential risks to the company’s sustainability. Any rational analysis of Facebook as an ESG investment should consider the complicated relationships among these risks.

Adding to this confusion is the ever-expanding range of sustainable investing strategies that are thematic in nature, prioritizing specific sectors or ESG factors, such as funds and indices that focus on areas such as renewable energy, Catholic values or gender equality. The underlying investments in these different strategies can vary wildly, in both how the portfolios are tilted and what sectors may be excluded.

With all this new capital and fund formation, potential problems are cropping up more frequently. While sustainable funds generally have lower ESG risk than the broad fund universe and vote in favor of key ESG shareholder resolutions, Morningstar notes that support of such measures varies widely. That may be an understatement. The SEC recently issued a risk alert examining the policies and procedures of firms claiming to engage in ESG investing, observing instances of potentially misleading statements around portfolio management, proxy voting, and marketing and disclosure practices – in a word, greenwashing.

The European Union, always a few steps ahead of the United States and other countries in sustainable investing, recently implemented anti-greenwashing investment legislation requiring money management firms with over 500 employees to state whether they are reviewing the impact of their investments based on 18 different ESG metrics. If, as seems likely, U.S. regulators follow a similar path, funds and corporations will likely revisit disclosures and business practices. And the number of data providers aggregating new ESG data and disclosures will continue to swell, hopefully making the marketplace for sustainable investing more transparent.

In the interim, investors have their work cut out in separating the wheat from the chaff in ensuring that customized portfolios accurately represent the values and goals of their clients. Comprehensive wealth advisory and financial planning focused on a family’s long-term plan – philanthropic goals, next-generation education and investment priorities – should help drive the investment decisions across asset classes.

Impact investing, which doesn’t just tilt toward or exclude ESG factors, but instead attempts to make investments that will have a more proactive impact, can be typically achieved through illiquid investment structures, which we will be reviewing in the next issue of Independent Thinking. We believe this approach can support both clear ESG goals and attractive returns. It’s also important to note that portfolio managers acting on behalf of families and institutions with ESG goals need to have a firm understanding of the fundamentals of the underlying investments, across all strategies, whether passive or active.

Performance, long the shadow hanging over the heads of many sustainable funds, is no longer a sore point for investors. The average sustainable fund has outperformed peers broadly over the last one-, three- and five- year periods, with the majority of funds in the first or second quartiles for performance (see the chart below), thanks in large part to technology and sustainable energy gains. 2 We believe the secular trends propelling ESG investing are likely to continue and even accelerate, as regulators and both corporate boards and executives turn their attention more and more to ESG factors, notably in support of a transition to a greener economy.

The result should be something of a virtuous circle, in which a company with a strong management team, a durable franchise, and good long-term growth prospects must be focused on long-term secular changes that impact their industry and all of their stakeholders. Companies that consider a long-term view as they make capital decisions and run their businesses day-to-day should be more likely to be more successful investments, from both a performance and a sustainability perspective. Customized portfolios of individual securities, mutual funds and illiquid investments can be designed around the values of individual families, foundations and endowments to deliver competitive returns to meet long-term ESG and financial goals.

Brian Pollak is a Partner and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].

1 Morningstar’s “Sustainable Funds U.S. Landscape Report” released in February 2021.

2 Morningstar.

The ABCs of SRI/ESG

Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) – The original definition of conscious investing, SRI tends to focus more on the passive avoidance of certain companies, most commonly referred to in relation to public companies. Portfolios can, for example, exclude companies with carbon-intensive operations or revenues derived significantly from tobacco, alcohol, gambling or handgun manufacture.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Investing – Investors utilizing ESG considerations in public markets act proactively, making both exclusionary and inclusionary decisions, and balancing the E, S and G considerations as they wish. For example, they can focus on environmental issues, avoiding carbon-intensive companies while investing in renewable energy. ESG factors are increasingly used as a lens in which to analyze potential private market investments.

- Environmental criteria relate to company actions on energy use, waste, pollution, natural resource conservation and animal treatment, to name a few. This approach also evaluates which environmental risks might affect a company’s income and how the company is managing those risks.

- Social criteria reference the company’s relationships, both internally and externally. An extensive range of issues are covered, including a company’s treatment of employees, its diversity and inclusion initiatives, and its charitable donations or stances on public issues.

- Governance in this context relates to the management of the company, and its system of rules, practices and processes – the ways in which a company balances the interests of all stakeholders, including shareholders, management, customers, suppliers, financiers, government and the community. Financial and accounting transparency, board of directors’ conflicts of interest, and executive compensation are also governance considerations.

Impact Investing – More commonly referenced in regard to private investments, these investments target measurable social or environmental outcomes to go along with a financial return. Asset classes for investment are wide ranging; project sizes can be big or small; and financial returns are varied. Affordable housing, microfinance, and resource scarcity are notable targets for impact investment, with tangible outcomes likely to measure low-cost units developed, a lowering of the “unbanked” population, and increased access to clean water.

Sustainable/Conscious/Responsible Investing – These terms encompass all modes of directing capital toward companies and projects in a thoughtful, conscious and repeatable way to deliver competitive returns while meeting an individual’s specific objectives.