Independent Thinking®

Taking the high road: Investing in America’s infrastructure

April 5, 2016

The United States has an infrastructure problem. Globally, the United States ranks 19th in the quality of its infrastructure.1 Quantifying infrastructure investment – and the related opportunities and risks – is a challenge, but is critically important in this election year, for our economy and our long-term competitiveness.

One place for investors to start is by looking at the amount of money the government spends on buildings and large-scale projects. Nationwide, public construction spending is just over 1.5% of our annual gross domestic product – the lowest since 1993. While the federal government’s monetary contribution to our infrastructure needs has steadily declined over time, it still holds significant sway over the critical approval process, which can add time and costs to any project.

Most of the money that is spent on public infrastructure comes from state and local governments, not from the federal government. As of 2015, more than 90% of the $291 billion spent by the public sector was at the state and local level, according to the latest Census Bureau report on construction spending.2

There should be opportunities for investors here. However, to date, debt hasn’t been issued in proportion to needs. With interest rates at record lows and improving fiscal conditions for most states, why aren’t states borrowing to spend on big capital projects? Part of the problem is that state and local governments remain heavily indebted. They are on the hook to pay pensions and benefits to retired government workers, and they borrowed a lot of money in the capital markets in the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis. As a result, they’ve been more focused on paying down debt than on investing in big capital projects.

There have been spurts of money dedicated by the federal government; most recently through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, or ARRA, of 2009, which was designed to provide temporary relief programs for those most affected by the recession and to invest in infrastructure, education, health and renewable energy. Of the ARRA’s total estimated cost of $831 billion, infrastructure investment totaled over $105 billion, a relative drop in the bucket. While this has provided some stimulus, it is no substitute for federal long-range planning and financing.

Focusing on Transportation Infrastructure

This critical system is in need of sustained investment. The growing burden of a weakening transportation infrastructure can be felt in poorly maintained and congested roads, structurally deficient bridges, outdated airports and seaports, weak passenger rail service, and inadequate public transportation. These problems result in unnecessary delays, damage to vehicles, and added costs for business and consumers. Furthermore, natural disasters, including Hurricane Katrina and, more recently, Superstorm Sandy, exposed the significant costs of inadequate infrastructure and demonstrated the need to improve resilience in the face of climate change.

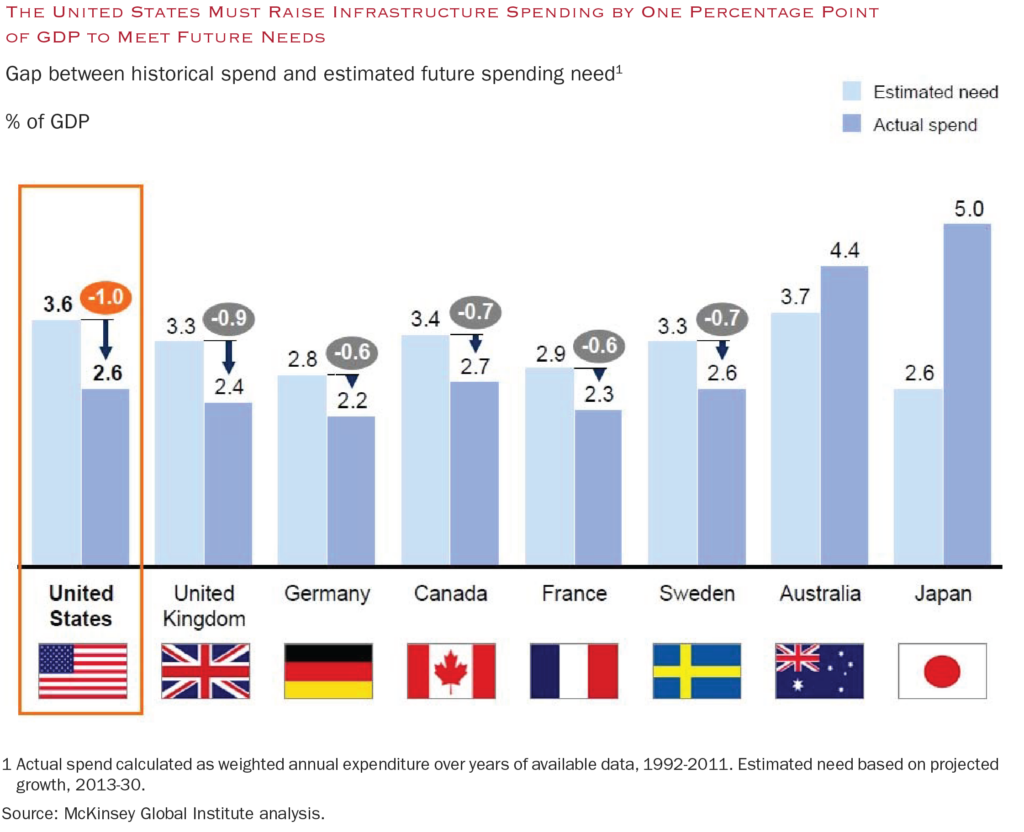

The United States needs to raise infrastructure spending by 1% of gross domestic product to meet future needs; more of a stretch than in many major western European countries, Australia and Japan. And while there was a temporary rise in 2009 due to the ARRA, spending has reached new lows, with little indication of increasing.

Simply put, lack of infrastructure investment today means inevitably greater future costs, as our systems continue to deteriorate. It also means man-hours lost to delay in traffic on overburdened systems.

The Approval Process

Any major infrastructure project requires various approval levels in order to ensure quality, safety, economics and efficiency. However, it takes just one trip to China, Germany, or just about any other industrialized country with high-speed railroads and gleaming new airports, to be disabused of any notion that we have superior infrastructure. The U.S. infrastructure system is so outdated that it will take some $2.2 trillion to fix, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers.3 And the approval process isn’t helping.

A well-intentioned effort in 1970 to consider the environmental impact of major infrastructure projects has become so drawn out that it has all but stopped vital improvements. The National Environmental Policy Act, intended to record the environmental consequences of projects and prevent abuses, has unfortunately taken on a life of its own, creating a series of regulatory administrative impediments that make it hard to build things. There are cases where any local group, any self-appointed person, can get involved with the process, threaten to sue, and demand more review.

The approval process for complicated projects is not strategically handled; it is comprised of silos. As highlighted in Gillian Tett’s book, The Silo Effect4 , the idea of silos, or developing expertise, can improve efficiencies but it can also lead to a narrow view along with bureaucratic rivalries and, ultimately, a delay in any project. For instance, to get approval for a new bridge or to work on an existing bridge, the government entity responsible for overseeing the project first needs environmental approvals, then a Clean Water Act permit from the Army Corp of Engineers for a Clean Water Act, and then a bridge permit from the Coast Guard. In many other countries, the equivalent agencies manage to work concurrently.

The Question of Finances

There are disagreements among U.S. government leaders – at the local, state and federal levels – over how to pay for new investments. These disagreements have contributed to a policy of inaction. One example of this malaise is the recent debate over Grant Anticipation Revenue Vehicles, or GARVEEs. (This is a federal funding program to leverage the federal gas tax through the Highway Trust Fund.)

On December 4, 2015, the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act, or FAST, was signed into law to increase federal transportation funding by 15% over the next five years, including an 18% increase in transit funding. The FAST Act transfers $70 billion, or about one-quarter of total spending over the five years, to the Highway Trust Fund, or HTF, from the federal government’s general fund. The HTF is funded by federal motor fuels and excise taxes. No long-term spending measure has been in place since 2009, which has led Congress to enact 35 short-term extensions. Deferring a long-term federal funding source for GARVEEs for six years has caused numerous project delays across the country.

However, the FAST Act does not address the HTF’s ongoing structural imbalance. Between 2008 and 2015, Congress transferred $72 billion into the HTF because taxes that flow into the fund currently amount to only three-quarters of its disbursements. Increasing motor vehicle fuel efficiency will further erode the structural balance by depressing gas tax revenues. In the interim, a growing U.S. population and economy will continue to pressure transportation spending upward.

Presidential Candidates and Their Policies for Transportation Infrastructure

The American Road & Transportation Builders Association published a special report in March discussing the remaining Presidential candidates’ position on funding transportation.5 As with many federally financed programs, there is a difference of opinion between the parties in not only the means to finance various projects, but also basic philosophy over the necessary levels of government involvement or interference, depending upon your point of view. Candidates Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton stress the job-creating potential of major infrastructure programs in the highway and transit funding proposals. They both propose financing sources derived from various tax reform measures. There is also sensitivity to the 18.4 cent per gallon federal gas tax during periods of rising oil prices. Any reduction to this tax and funding for the Highway Trust Fund would be made up by raising taxes on the oil industry. Senator Sanders voted for the FAST Act. Secretary Clinton also supported passage.

Republican candidate Senator Ted Cruz has consistently supported devolution proposals of the federal gas tax and voted against passage of the FAST Act. When in Congress, Governor Kasich sponsored several proposals to reduce the federal gasoline tax to a few pennies per gallon. The idea is that, with a federal gas tax reduction, states have more flexibility to increase their own gas tax or find other funding sources to accommodate their infrastructure needs, while reducing the federal transportation bureaucracy. However, to date, many states have been unwilling or unable to support financing proposals for transportation, even with the overall recent lowering of the price of gas.

New York businessman Donald Trump said infrastructure modernization would be one of his top priorities as president, although he has provided few specifics about how to finance the realization of this vision.

Options to Fund Transportation Infrastructure and Investment Opportunities

The problem is clear. The challenge has been finding a politically viable solution to pay for this investment, as well as better coordination in approving projects to reduce costs. New or varied financing sources also provide investment opportunities and risks. The legal structures associated with these potential bond offerings are also important to prevent overleveraging of volatile revenue sources. These options include the following:

- State and local gas tax: All states and some localities have a separate gas tax, in addition to the 18.4 cent federal gas tax. This tax is often leveraged to secure debt. Since the price of gasoline has dropped precipitously over the past two years, now would seem to be a good opportunity to increase the tax and, perhaps, increase the future tax rate by linking it to the inflation rate in order to maintain its funding power. Over the long haul, however, gas taxes may no longer provide sufficient purchasing power as cars become more fuel efficient, young people opt for mass transit in the congested cities that have become more desirable, and vehicles potentially use other fuel sources such as electricity. An alternative to taxing fuel per gallon is to tax vehicles per mile driven. The technology exists to monitor mileage; Oregon has already launched a pilot program to test the efficacy of this approach.6

- Motor vehicle receipts, licensing fees and permits: These monies are typically used to fund state Highway Trust Accounts that can either be leveraged and/or used on pay-as-you-go financing projects. Again, a mechanism to adjust for inflation would retain the purchasing power. However, a larger issue is protecting these funds for transportation projects and legally preventing monies from being diverted to non-transportation issues (i.e., balancing a state’s operating budget) during difficult fiscal times. It is important to create this “lock-box” mechanism to protect the integrity of the transportation infrastructure program. Concerns also extend to diverting toll revenues from the specific enterprise system to broader transportation needs in order to avoid raising other taxes. An example of this is the Pennsylvania Turnpike Authority.

- Expanding authorization for design-build contracts: Delays and cost overruns are very common in public sector infrastructure projects. Facing these challenges, some states have turned to design-build and other, more integrative, procurement strategies. Design-build eschews the traditional “design-bid-build” process of separate, sequential contracts for each phase of the project. Instead, responsibility for design and construction are bundled together in a single contract, often awarded on the basis on the best perceived value rather than lowest cost.7 Typically, a design-builder commits to a total cost specified in a contract, thereby assuming most of the risk associated with delays and cost overruns. Collaboration between design and construction teams avoids costly change orders in the middle of construction; construction work can begin before designs are completed; experience on the ground informs the final designs; and all parties can cooperate to offer innovative solutions to challenges as they arise – without waiting for bureaucratic approval.

- Public-Private-Partnerships, or P3s: A P3 is a contractual partnership between a public sector governmental entity and a private developer to design, build, finance, operate and maintain an infrastructure asset for a specific period. At the end of the contractual period, the asset reverts back to the government to operate and maintain. The government generally maintains ownership of the asset throughout the contract terms. Governments are under pressure to keep spending in check, as well as insulate long-term maintenance and capital investment from the political cycle, since capital spending is typically cut during times of austerity, reducing the asset’s useful life.

- Value Capture and Rights-of-Way: Transportation improvements create numerous economic, social and environmental benefits, not only for travelers, but also for the owners and developers of nearby property. The value of these benefits come in the form of higher land values and corresponding enhanced development opportunities. Value capture means recovering a portion of these gains to help fund transportation improvements, thereby reducing the total cost to taxpayers. In New York City, the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation was formed with the expectation of real estate development and the increase in various property tax receipts used to support the extension of a subway line running through the new development.

- All-Electronic Tolling System and Congestion Mitigation: An All-Electronic Tolling, or AET, system can eliminate toll plazas, with tolls collected from vehicles at full highway speed. With an AET, toll rates during peak periods can be set higher than those in the off-peak periods (known as congestion or value pricing). Many states have proposed roadway investment located in just a few of the major highway corridors in their state. Implementing corridor-wide AET in those roadways will directly link new AET revenues to those areas where major investments are being made. In these cases, the toll is directly charged to the users who benefit from the major investments.

Conclusion

Investors know that the need for improving the infrastructure in the United States is clear and critical. Vehicles for investment are more elusive. Our analysis in pursuing the bonds secured by various financing options is based on several factors: the volatility of the revenue stream, the construction and operating risk of specific projects, the underlying economics while providing safeguards against over leverage through various legal protections found in the documents. Our portfolios contain many transportation infrastructure bonds secured by traditional revenue streams including tolls, gas, excise and sales taxes, and various motor vehicle receipts such as the New York State Thruway and the Oregon Department of Transportation Highway User Tax Revenue Bonds. Some portfolios can also consider carefully researched public-private-partnerships or bonds that have been secured by an increase in property values derived from the transportation improvements, such as the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation. These changes will continue as the infrastructure needs only grow, and financial resources are limited by political considerations. Continued conversations with our clients help us assess their risk appetite in this rapidly evolving sector.

Howard Cure is the Director of Municipal Research at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at: [email protected].

1World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, 2014-15

2US Census Bureau, “Annual Value of Public Construction Put in Place 2008-2015”

3America Society of Civil Engineers 2013 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure

4Gillian Tett, “The Silo Effect: The Peril of Expertise and the Promise of Breaking Down Barriers,” 2015

5American Road & Transportation Builders Association Special Report: The Presidential Candidates on Transportation March 2016 Edition

6The Hamilton Project: Financing US Transportation Infrastructure in the 21st Century discusses whether or not a greater reliance on user fees disproportionately burdens lower-income individuals. They argue that the benefits of infrastructure are distributed relatively progressively; the regressivity of user fees may be lessened. This is based on infrastructure jobs created, less road congestion and subsidization of public transit.

7Best value contracts allow for the consideration of other important criteria besides cost, such as prior experience and performance.