Independent Thinking®

A (Temporary) Breach in the Defensive Line: Municipal Bonds

March 28, 2020

We do not believe that municipal bond credit risks justify the continued high yields relative to Treasuries. First, a brief recap. After 60 consecutive weeks of inflow into municipal bond funds averaging $2 billion a week, sentiment shifted at the end of February as the fallout from COVID-19 reached all asset classes. As investor sentiment changed, redemptions out of the municipal bond mutual funds rose to $12 billion from $250 million in three short weeks. Municipal bonds, like Treasuries, are defensive assets, meant to provide safety and stability to portfolios in periods of volatility in the equity market. But this forced selling, along with a related unwinding of leverage by municipal bond funds and speculative investors, temporarily restricted municipal bond liquidity and drove municipal bond prices lower, disrupting the usual relationships between the asset classes.*

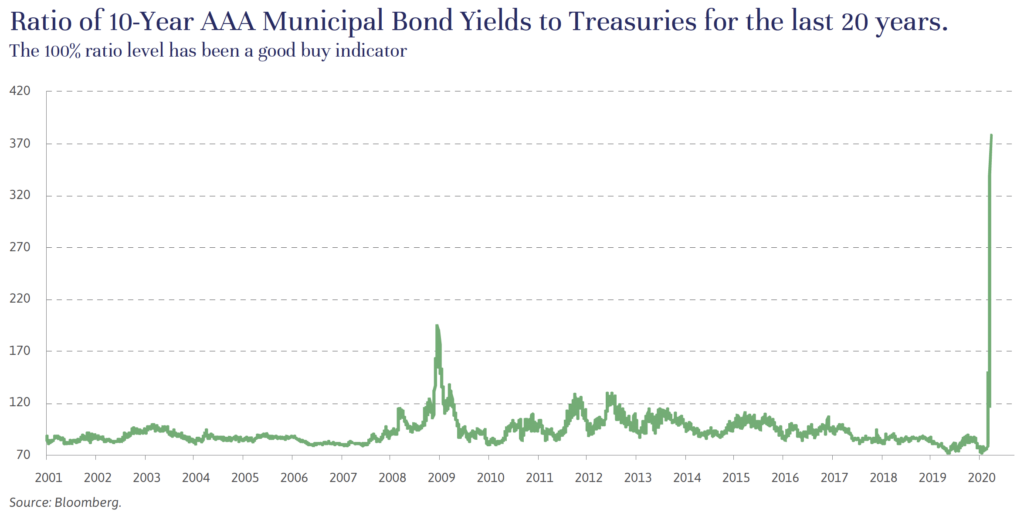

The relationship is being restored. The benchmark Bloomberg Barclays Managed Money Short/Intermediate Total Return index has, as of March 26, recovered most of its losses, after falling by as much as 9.6% in 10 days from its peak on March 9, 2020. However, municipal bond yields remain extreme, at more than double the 100% buy indicator level, and even higher than levels reached during the financial crisis of 2008.

Generally, when the ratio between 10-year AAA rated municipal and Treasury yields rises above 100%, municipal bonds are considered attractive since they are tax exempt at the federal and usually state level, whereas Treasury bonds are taxable at the federal level and only tax exempt at the state level. As the chart below shows, the 100% ratio level has been a good buy indicator.

We expect that the ratio will revert back to its sub-100% historical norm over the near term as doomsday credit concerns prove to be unrealistic and demand returns to the market, since municipal bonds provide investors relative value to other fixed income products due to their tax-exemption and generally higher credit quality. In the interim, investors familiar with municipal bond credits, such as banks, insurance companies and wealth management firms, are beginning to aggressively buy municipal bonds, given their relative safety and attractiveness at current levels.

But what about the municipal credit implications of the coronavirus? The rapid spread of the coronavirus has led to extensive business closures, sudden high unemployment numbers, and unprecedented restrictions on social interactions. It will result in a significant decline in economic activity – likely a recession. But state and municipal governments, and their public enterprise systems, have dealt with economic recessions in the past and have, for the most part during prior recessionary periods, continued to provide needed services while repaying debt in full and on time.

For the municipal bond market, this is different from the financial crisis in 2008-2009 when the economy went into a recession; the auction rate market was eliminated; investment banks needed a federal bailout; and most monoline bond insurers were essentially rendered inoperable. Since the Great Recession, states and municipalities have made significant improvements to their operating budgets and liability profiles, refinanced their outstanding debt at lower rates, and improved funding of their operating reserves. So today, states and municipalities as a whole are financially stronger than at the inception of the Great Recession and will be facing the economic-related headwinds resulting from COVID-19 from this position of strength.

Municipal bond sectors cover the spectrum of state and local operations and are funded through a variety of taxes and fees, so the credit impact on different municipal bond sectors will depend on the severity and duration of the outbreak in a particular location. The source of funding for operations and, ultimately, the payment of debt service, is key to determining the vulnerability of each sector. Sectors that are generally less vulnerable to an immediate impact from a COVID-19 related economic slowdown include:

- Essential purpose enterprises, including public water, sewer and electric utilities.

- General obligation debt for states and cities, counties and school districts that derive the majority of their revenues from some combination of property taxes and state aid.

- Dedicated tax bonds deriving security from sales taxes.

- State housing agencies with mortgage payments that also benefit from federal guarantees.

Sectors that will endure more extended interruptions in revenues will include the transportation-related, such as toll roads, airports and ports; higher education; and healthcare. These sectors derive revenues in enterprises whose operations have been severely curtailed or have their operations put under financial strain. However, our holdings in these sectors serve a highly valuable public service; generally have additional reserves such as cash and debt service reserve funds; and have ability to draw on lines of credits with banks to raise additional liquidity to weather an extended interruption.

Looking a little deeper into two of the aforementioned sectors – airports and toll roads – that we believe will most immediately be affected, we are comforted by the strength of the median borrower’s balance sheet. Debt issuers with greater liquidity – cash reserves and availability under long-term committed bank facilities – will be best positioned to independently weather the immediate economic fallout from the outbreak. According to Moody’s Investors Service, the median airport and toll road borrowers have enough cash reserves to operate nearly two years and over two-and-a-half years respectively without collecting any revenues.1

It’s important to stress that municipal bond issuers as a whole endure challenging economic conditions. Unlike other fixed income credit markets, defaults are extremely rare in the municipal market. Moody’s Investors Service reports that the average five-year U.S. municipal default rate from 2009 through 2018 has been just 0.16% and only 0.09% since 1970.

Furthermore, the economic distress – existing and still in the making – caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is inspiring bipartisan recognition at the federal level that the states are on the frontline in responding to the health crisis, and will experience revenue declines and spending increases. We are still working through the details of the $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Stabilization Act, or CARES Act. Early indications are that the plan will slow, but not eliminate, a fiscal imbalance in state budgets. We will be writing more about the CARES Act; at present it looks like a good first step in relieving the severe fiscal burdens faced by state and local governments but is likely to fall short of what is needed to both combat the virus and balance operating budgets. Its passage may make it easier to pass another relief stimulus or a spending package, if needed. The federal government is demonstrating a willingness to directly help the states’ and enterprise systems’ fiscal situation.

Our holdings were purchased subject to our stringent credit standards because they had adequate security and resources to make payments during disruptive periods. In this very fluid situation, we continue to vigilantly monitor our existing holdings and are taking advantage of the current opportunities to increase yield (i.e. income) in portfolios as appropriate.

Steven Chung is a Managing Director and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Howard Cure is the firm’s Director of Municipal Bond Research. He can be contacted at [email protected].

*Bond yields and prices are inversely related. As bond yields fall, prices increase and vice versa.

1 Moody’s Investors Service shows median airport borrower with 659 days cash on hand (DCOH)and toll road borrowers with 914 DCOH. Days cash on hand: Unrestricted cash and investments plus discretionary reserves divided by operating and maintenance expenditures and multiplied by 365 (does not include debt service reserve funds).