Independent Thinking®

The Case for U.S. Bonds

July 21, 2016

Investors around the world have flocked to U.S. bond markets in search of yield and, since Britain’s referendum vote to quit the European Union, safety. Certainly, the U.S. fixed income sector stands out against the very low, or even negative, yields in other developed nations.

Almost 60% of the Bank of America Merrill Lynch Global Government Bond Index, excluding U.S. bonds, trades at a negative yield, and about one-third trades at a yield that is less than 1%. Japan’s 20-year yield briefly dropped past zero for the first time, and as of writing, the U.S. Treasury 10-year yield is currently 1.58%, near record lows.

Investors have embraced municipal bonds in an otherwise unsettled time for financial markets, as evidenced by substantial retail inflows into the asset class this year. Municipal bonds currently offer some of the highest yields for U.S. residents, when adjusted for taxes. In fact, yields on municipal securities are sometimes higher than yields on similarly rated taxable debt even before taxes are considered. A carefully selected portfolio of high-grade municipal bonds can include tax exemption, high credit quality, liquidity and relatively low volatility.

Other than a handful of issuers in the headlines, notably Puerto Rico, municipal bonds have fared well. The Barclay’s Managed Money Short/Intermediate Index has returned 2.88% year-to-date through June 30. While this partly reflects recent declines in U.S. Treasury yields, it also reflects the strong supply and demand characteristics of municipal bonds, along with steady credit quality for the overall market. That’s likely to remain the case: Maturing bonds and bonds that are expected to be called by issuers are projected to outweigh the anticipated volume of the new supply of municipal bonds in the coming months. We expect that municipal bonds will remain an attractive fixed income alternative for U.S. taxpayers. However, investors should be aware that the income they will earn in this low interest rate environment will be significantly less than the income they may have enjoyed just a few short years ago.

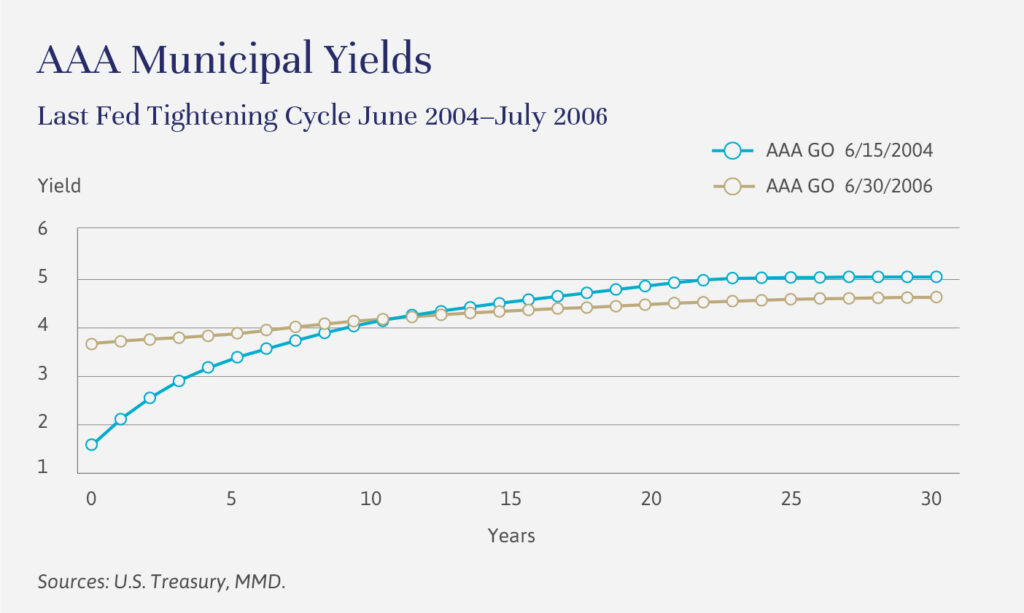

At some point, short-term interest rates are likely to rise, an eventuality that worries investors in bonds. After all, the Federal Reserve’s stated intention is still to raise its target range for the federal funds rate over time, and it seems to us that economic conditions will eventually warrant this tightening of policy. However, the Fed’s stated intention is for the pace of rate hikes to be gradual. It’s also worth noting that bond markets fared well during the Fed’s last tightening cycle, which began in June 2004 and concluded in June 2006.

That cycle was characterized by slow, well-telegraphed increases in the federal funds rate, features that could also prevail in this cycle. During the 2004-2006 cycle, yields at the short end of the municipals curve rose, as one would expect. Investors in short maturity bonds would have been able to reinvest the proceeds in higher-yielding securities as their bonds matured over time. However, yields further out the curve, beyond ten years, actually were lower by the end of the cycle, reflecting the market’s expectation that tighter monetary policy would contain inflation and eventually slow the pace of economic growth. If a bondholder stayed the course during this cycle and remained invested in the longer bonds, yields on their bonds would have declined and the price would have improved.

While the result of this analysis is encouraging for bond investors, not all tightening cycles are the same with respect to the timing, duration, and magnitude of the increases. And not all tightening cycles affect the shape of the curve in the same way. But the yield curve typically flattens during tightening cycles, with short-term rates rising much more than long-term ones. Often the coupon payments of longer dated bonds will offset, or go a long way to offset, the price decline.

History suggests that investing in bonds during a tightening cycle does not necessarily end in disaster, as long as a portfolio is positioned properly for the change. As interest rates are difficult to predict, a diversified approach would help investors through the uncertainty. A barbell strategy, for example, with exposure to both the short and the long ends of the yield curve, can be effective. In this case, the shorter maturity securities earn ever-higher yields as the Fed tightens, but the longer dated bonds generate more income and provide a hedge against the possibility that rate increases turn out to be anemic.

Sandy Panetta is a Partner and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. She can be contacted at [email protected].