Independent Thinking®

The Fiscal Deficit and Federal Debt: How Did They Get So Big?

November 7, 2018

In 1789, Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton had a great battle over how to treat the enormous debt that had been run up by the individual states during the Revolutionary War. Hamilton wanted the federal government to assume the debts of each state government by creating a national debt, while Jefferson argued for each state to carry its debt independently, and for rigid limits on the amount the federal government could borrow and for how long. As theatergoers know, Hamilton’s argument won the day, and the newly established United States Treasury issued a bond totaling about $75 million.

All of the founding fathers, including Hamilton, had concerns about excessive debt and viewed borrowing primarily as a mechanism to fund wars and extraordinary items. (Jefferson later authorized debt to finance the Louisiana Purchase.) George Washington summed up the founders’ perspective on debt by advising the new country to “cherish public credit.” He added: “One method of preserving it is to use it as sparingly as possible.”

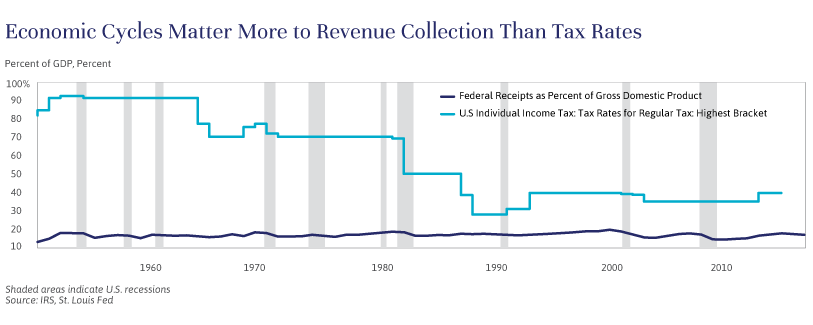

From 1789 until the early 1980s, the national debt held by the public generally stayed below 25% of GDP, apart from times of war or economic calamity. After World War II, which left the United States the only undamaged major economy, the U.S. dollar became the pre-eminent global reserve currency, the one in which other governments hold dominant portions of their financial reserves, as well as the preferred medium of exchange for international commercial transactions and the unit in which commodities are typically priced.

The dollar’s rise to global reserve currency status set the table for a shift in economic policy around the fiscal deficit and national debt. Starting in the 1980s under President Reagan, the United States experienced its first persistent and significant peacetime deficits. Apart from a few years during President Clinton’s tenure, these deficits have continued. Today, for the first time, we have a rising deficit as a percentage of GDP during a period of both relative peace and economic prosperity.

Some economists argue that’s not as alarming as it sounds. After all, Japan, which doesn’t have the benefit of a global reserve currency, has been able to sustain a high deficit and debt load for decades, and is currently saddled with a debt of over 200% of GDP. Yields on 10-year Japanese government bonds remain close to 0% and, while growth is slow, there has yet to be an economic reckoning. Japan’s experience offers no guarantee for the future of the United States, but it does at least raise the possibility that significant problems related to the debt may still be some way off.

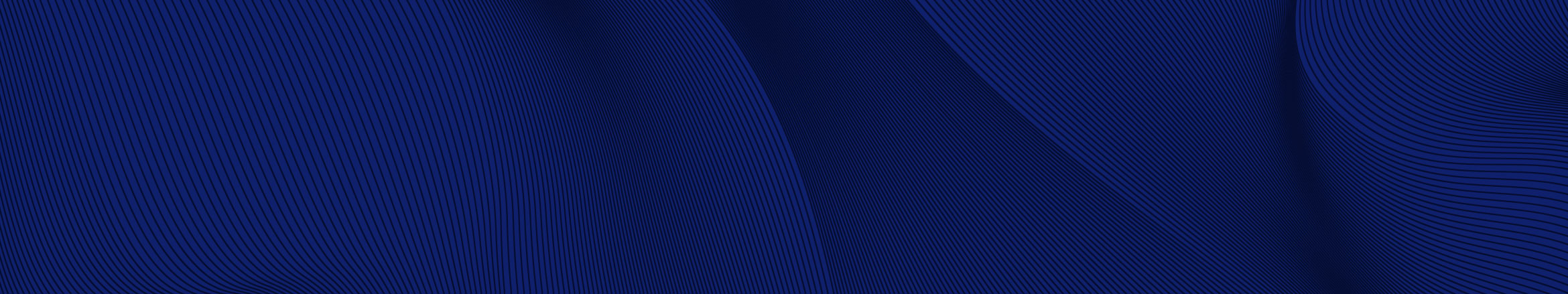

Most economists and long-term investors would prefer to see the U.S. debt addressed. That’s easier said than done. While it is possible to reduce the annual deficit somewhat through a reduction of discretionary spending (the part of the budget not devoted to entitlements, defense or debt payments), or an increase in tax receipts, a deeper analysis of the deficit suggests that tackling entitlement spending is the only way to get the deficit under control over the long-term. Mandatory spending on Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and similar programs currently accounts for over 60% of federal outlays, and the proportion is rising, due to an increase in benefits and an aging population. Together with these mandatory spending commitments, defense spending, which takes up another 15% of total outlays, and interest expenses at about 7% of GDP and rising, nearly 100% of government receipts are used up, as shown in the charts below. This essentially leaves all the remaining government programs to be funded by deficit spending, which ranges from paying for the Justice Department and White House staff to federally funded infrastructure investments.

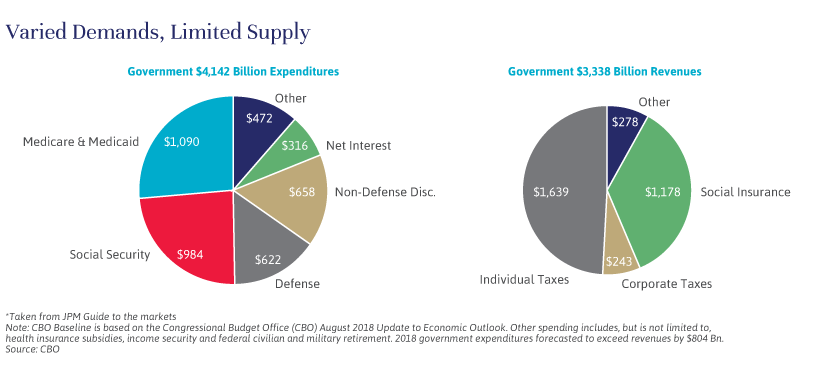

Higher tax rates and more careful discretionary spending, when combined, could have some impact on reducing the deficit from its projected trillion-dollar level, but would be unlikely to reduce it materially. As illustrated since the 1960s and by the graph below, individual and corporate tax rates matter, but only marginally. Regardless of the prevailing tax regime, total tax receipts come in within a fairly small percentage range relative to GDP, and rises and falls in tax receipts are more correlated to the economic cycle.

An increase in economic growth and/or inflation is more likely to bring debt under control. If nominal GDP growth outstrips the growth in the debt over a prolonged period of time, the percentage of debt to GDP will shrink to more normal levels. However, many economists believe that significant and prolonged nominal economic growth is unlikely due to the U.S. demographic profile.

This leaves entitlement spending reform as the only realistic long-term solution to reduce the deficit. But cutting entitlements would require political will that is not currently in evidence. This administration appears to view entitlements as sacrosanct, while the opposition, especially the more liberal wing of the Democratic Party, is interested in further entitlement expansion.

It is difficult to know what either Jefferson or Hamilton would make of our current circumstances. The longer our fiscal deficit persists, the more Treasuries the federal government will be forced to issue, and the greater our reliance will be on our status as the dominant global reserve currency. We are mindful that it is difficult to invest around the potential timing of a government debt-related crisis, but are confident that a well-constructed portfolio of diversified investments will remain important in mitigating economic risk.

A Troubled Relationship

The federal debt and the fiscal deficit are related. The deficit is the difference between the amount of revenue the government collects in a given year, primarily from taxes, and the amount it spends on entitlement programs, defense spending, debt servicing, and other outlays. When government spending outstrips revenues in a given year, there is a fiscal deficit that must be funded with new debt, mainly U.S. Treasuries. The net new issues add to the federal debt, which is typically measured in aggregate, relative to the gross domestic product or GDP. That ratio has been rising, and that rise, as illustrated here, is projected to continue.

Brian Pollak is a Partner and Portfolio Manager at Evercore Wealth Management. He can be contacted at [email protected].